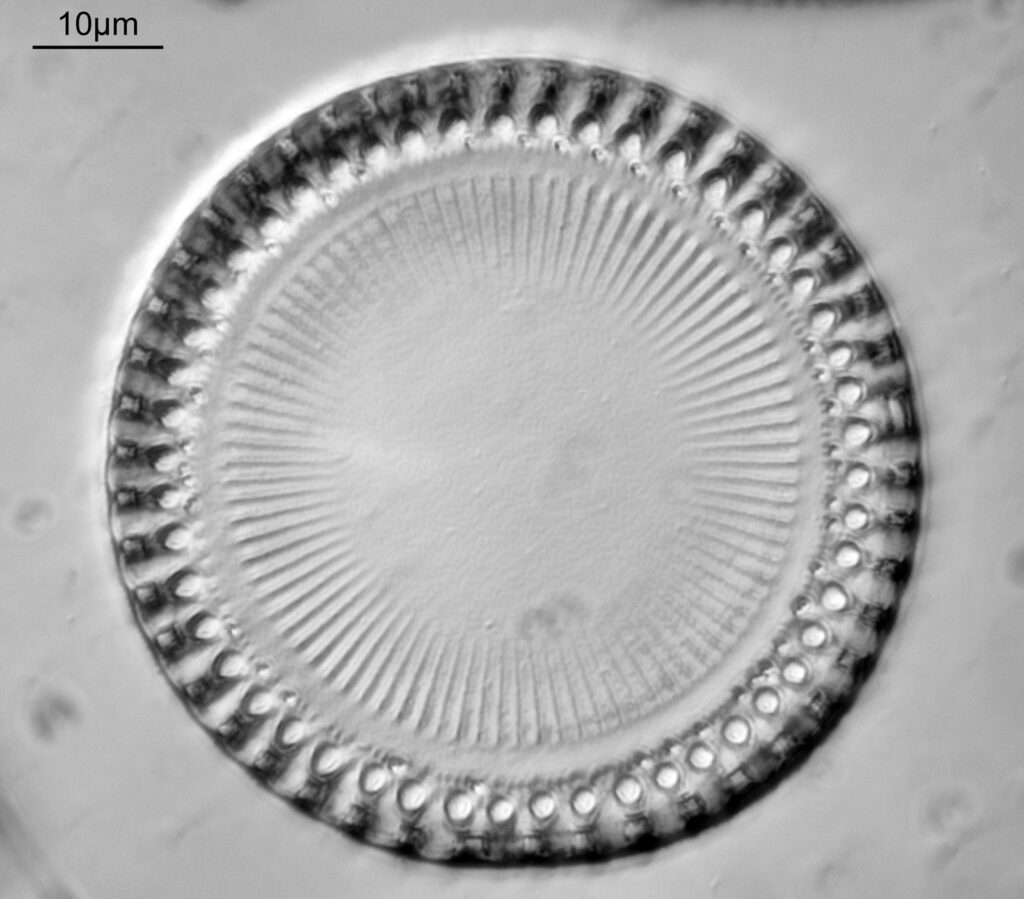

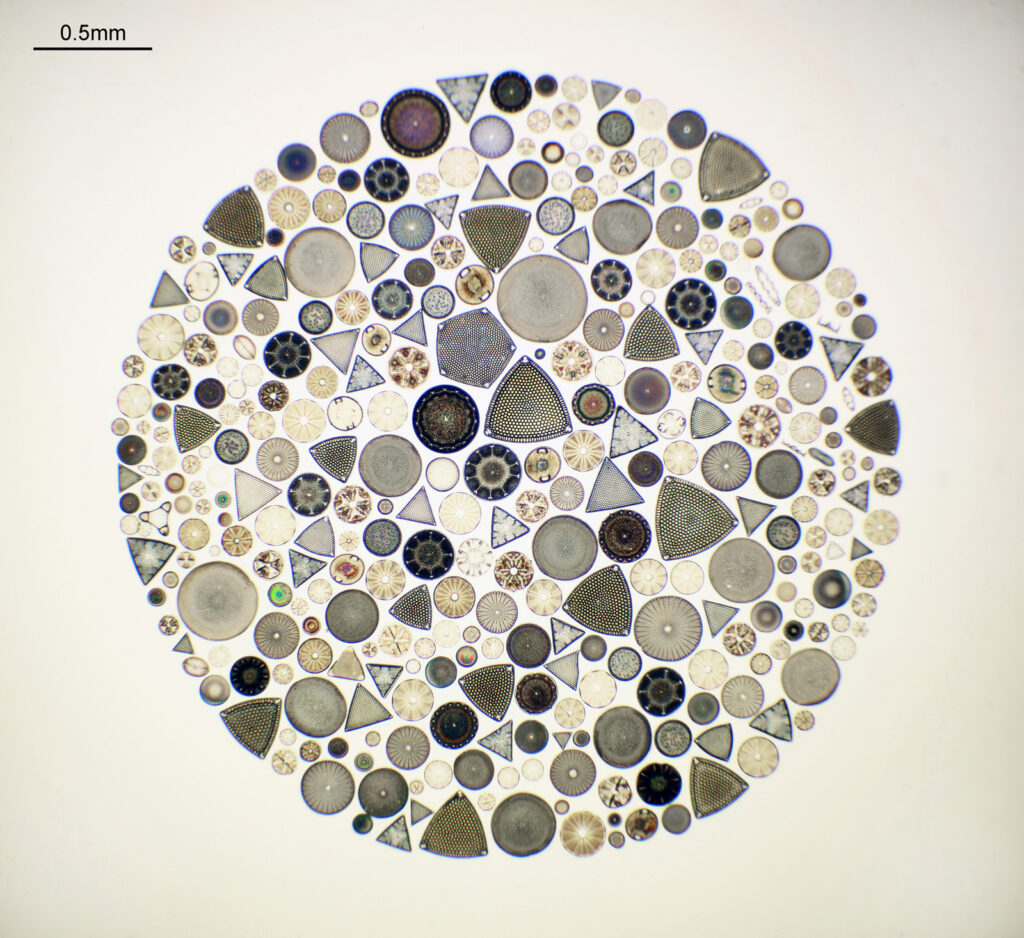

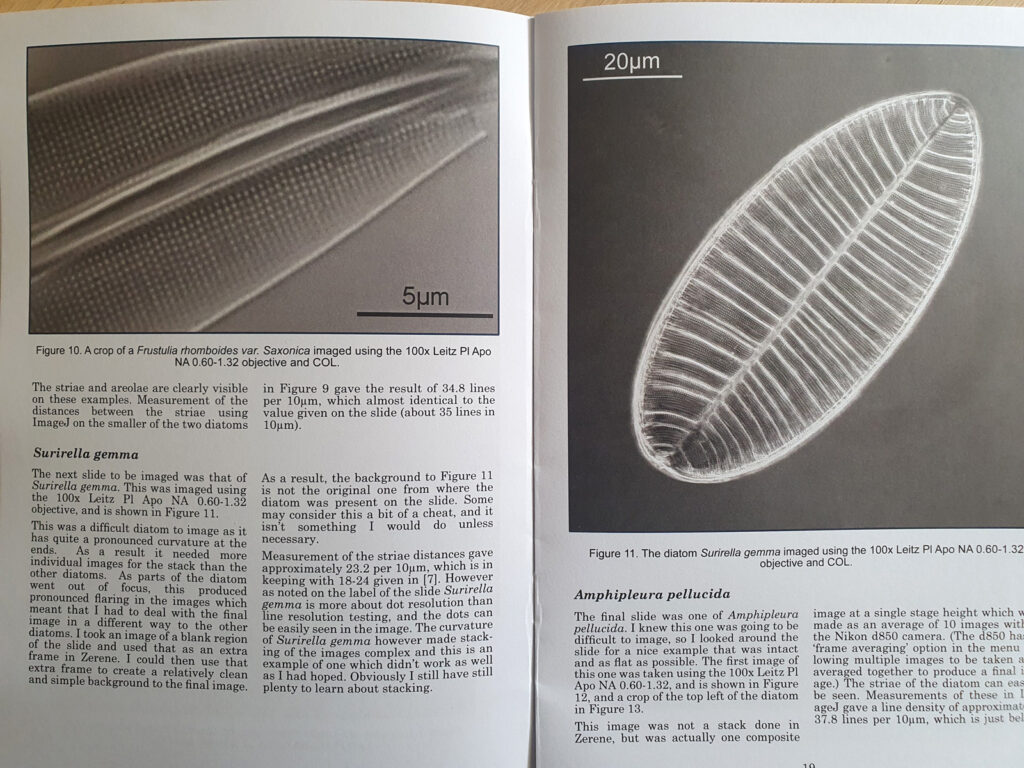

You can find find diatoms pretty much anywhere, but the range present at one location can be very different to other places. Toome Bridge (now called Toome or Toomebridge) in Ireland is a place which seems to have an amazing array of photogenic diatom species in the diatomite that is mined there. I have a couple of strew slides from that location and today’s post will show some images from one of those.

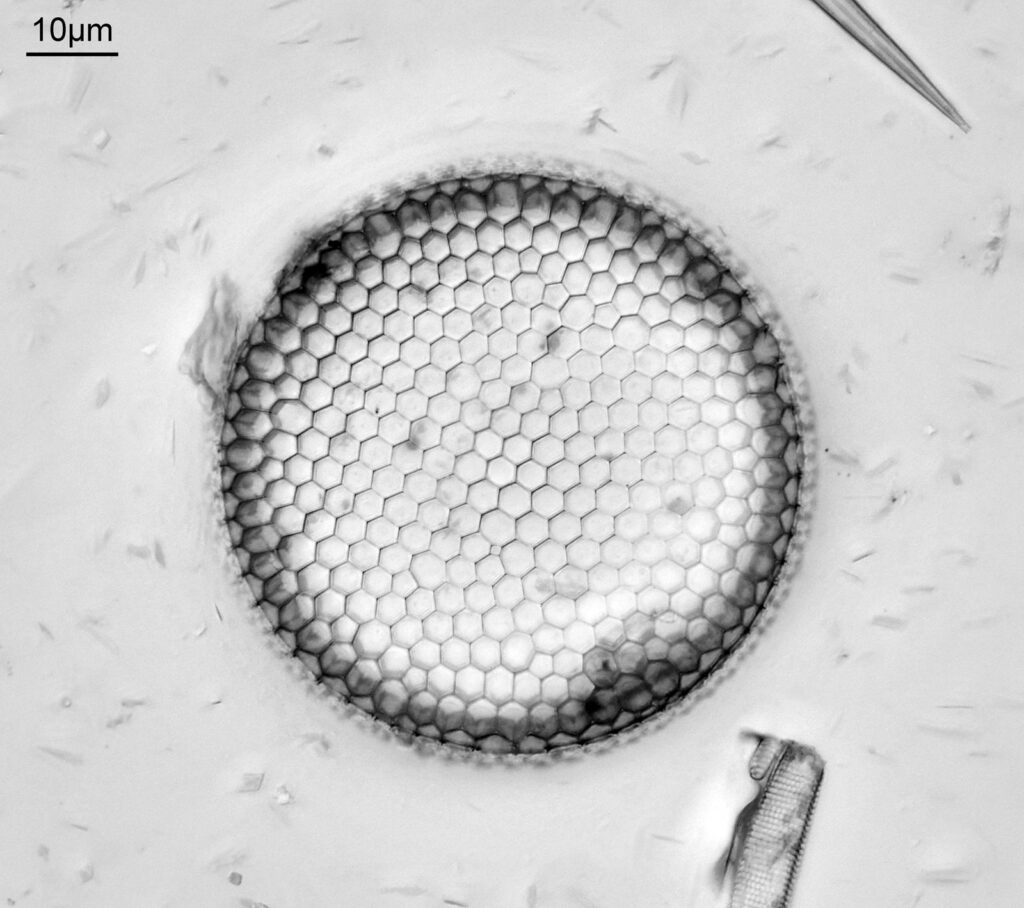

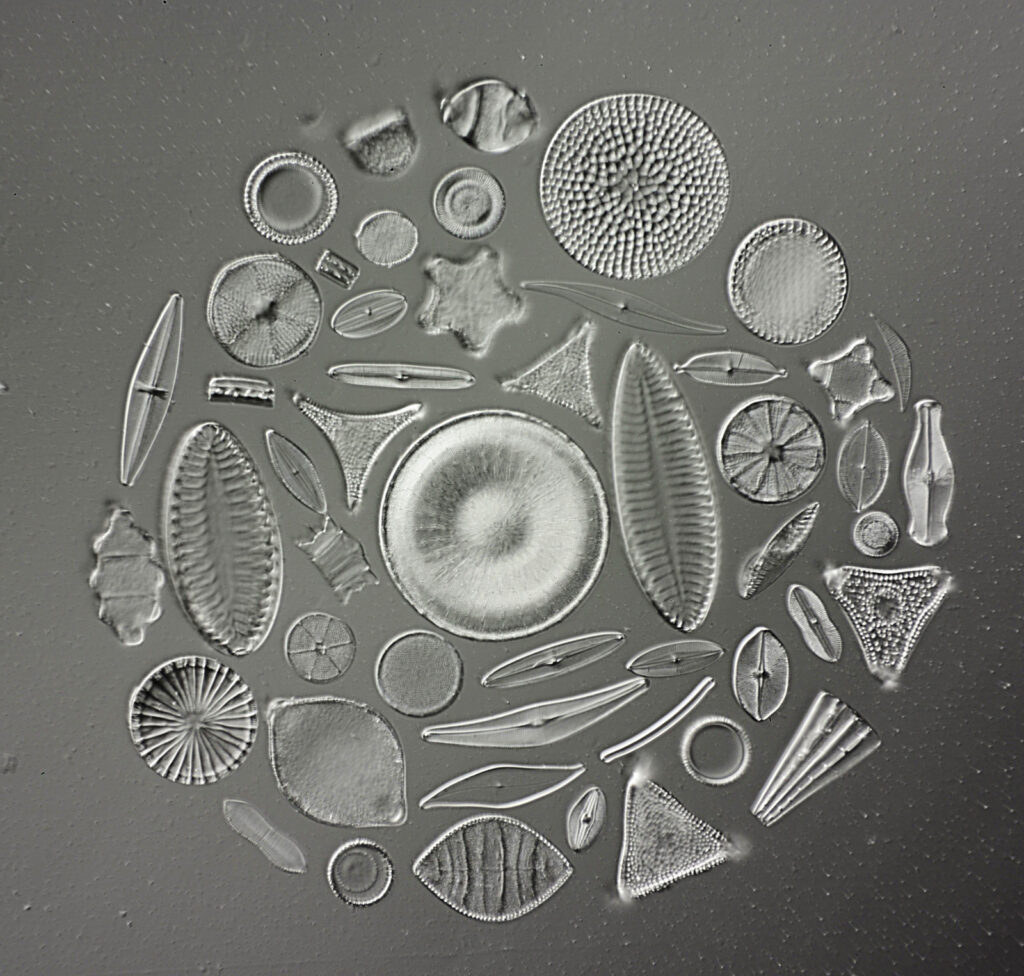

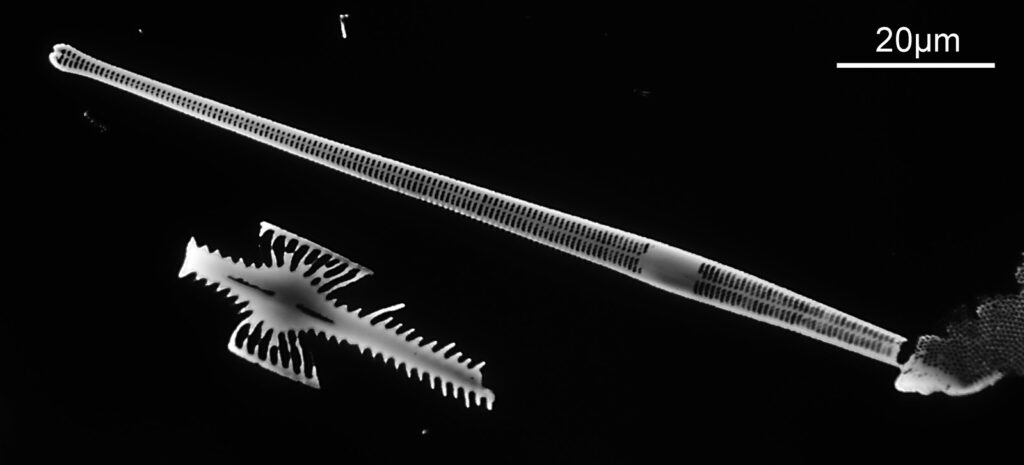

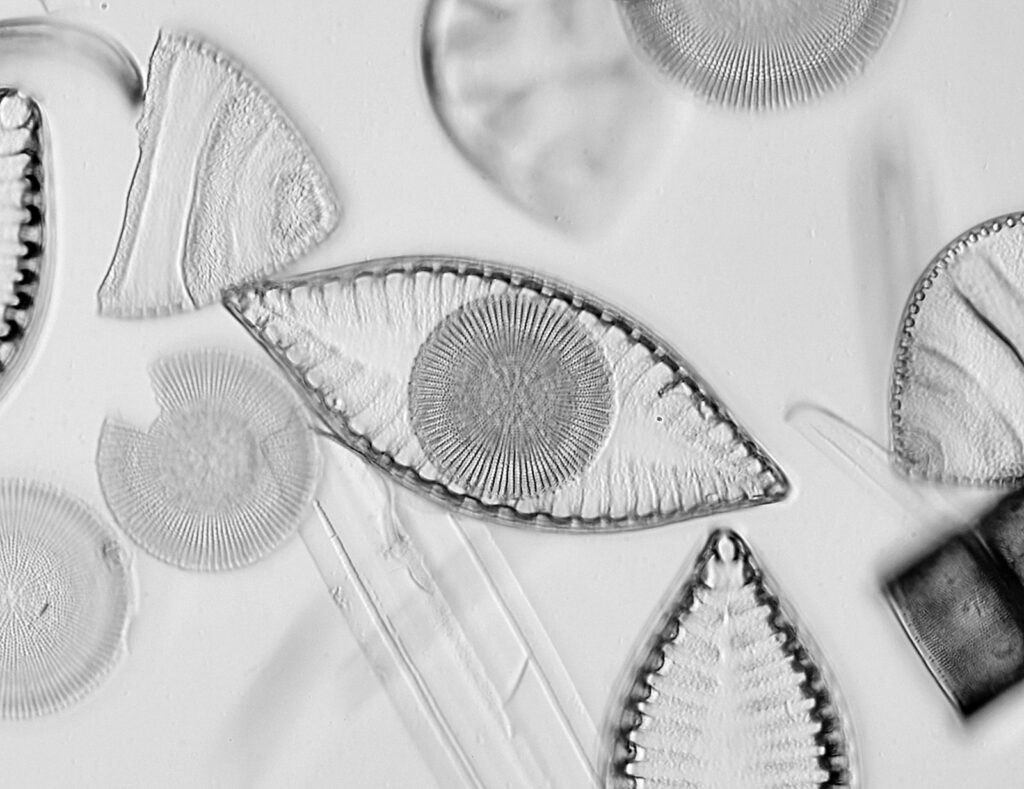

This slide was made by Neville Bradpiece, with diatoms mounted in Sirax. Apologies, but I don’t have names for all of these different species, but I have added names where I can. Some of the images have been reduced in resolution for sharing here. To start with, the eye…..

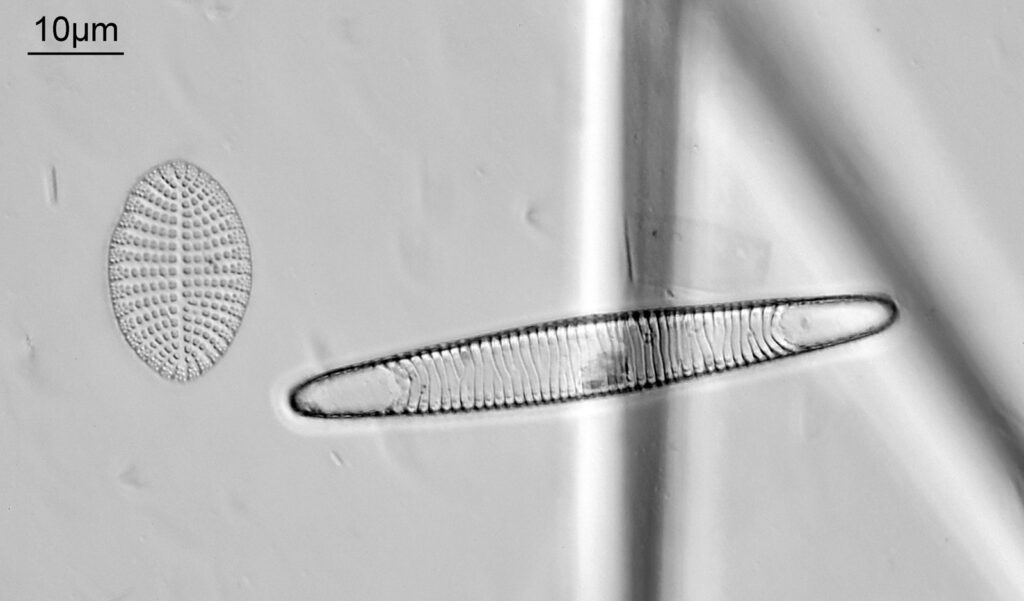

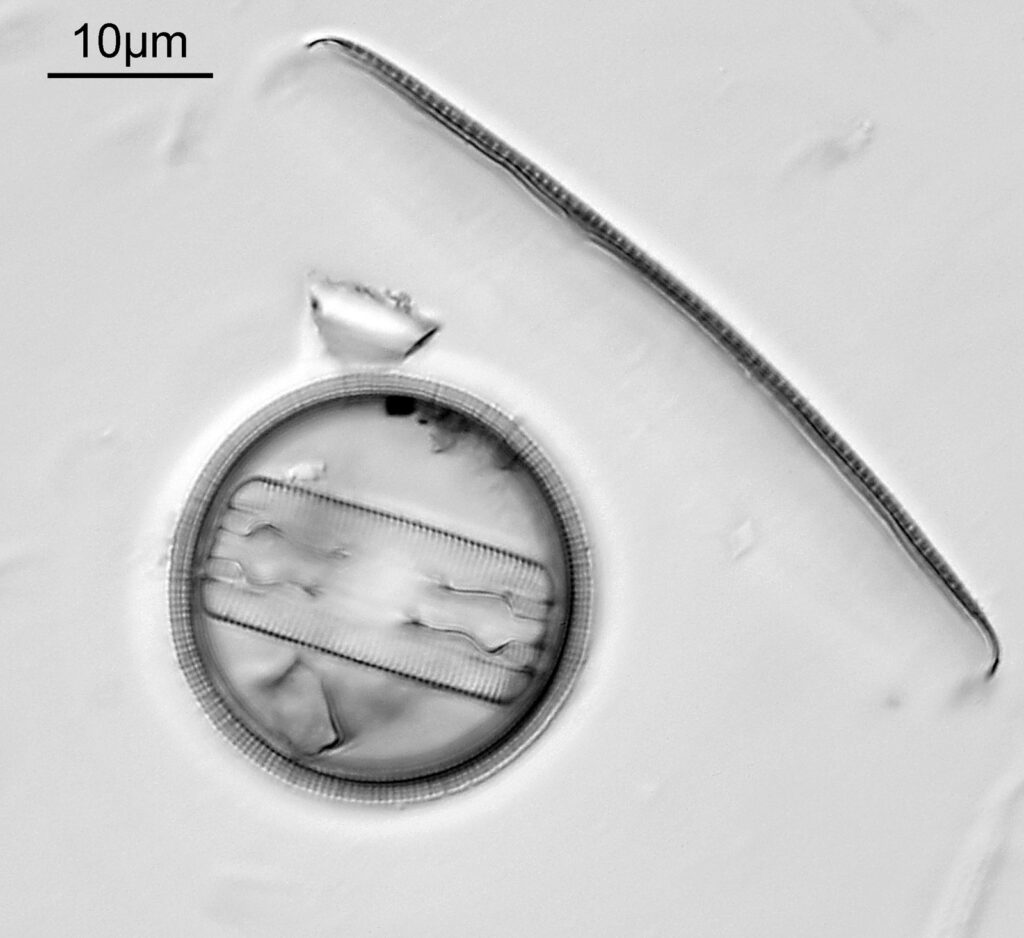

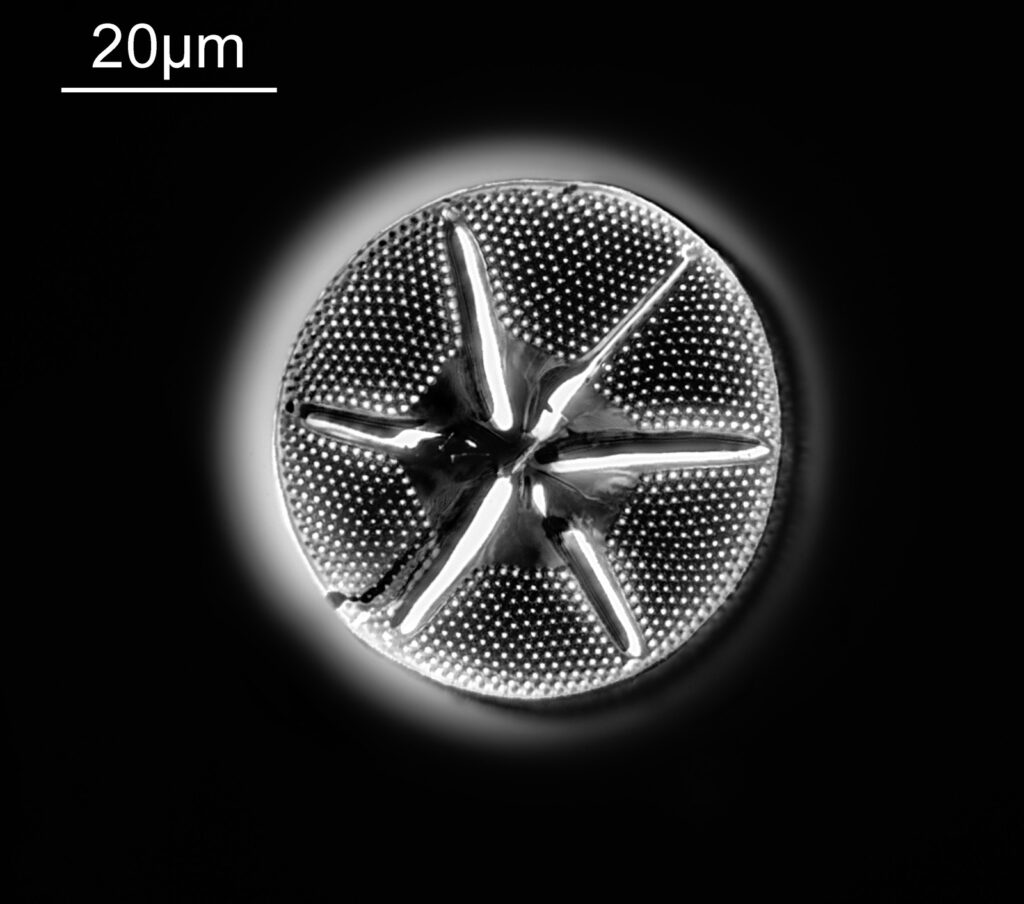

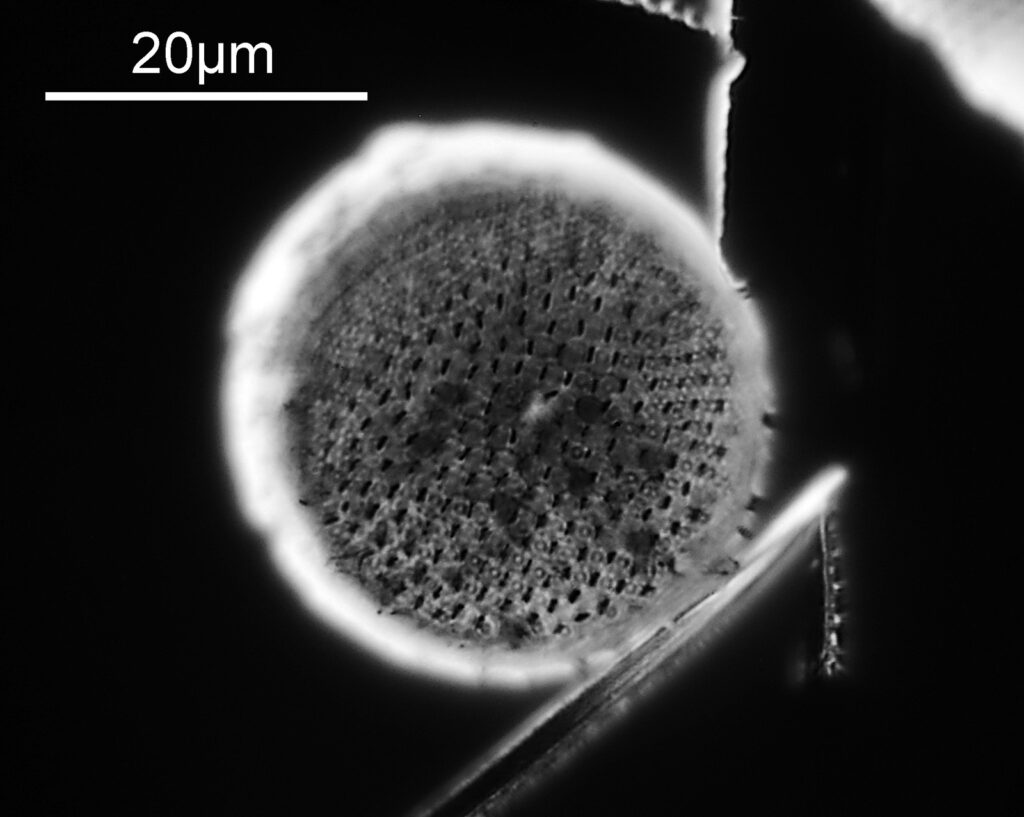

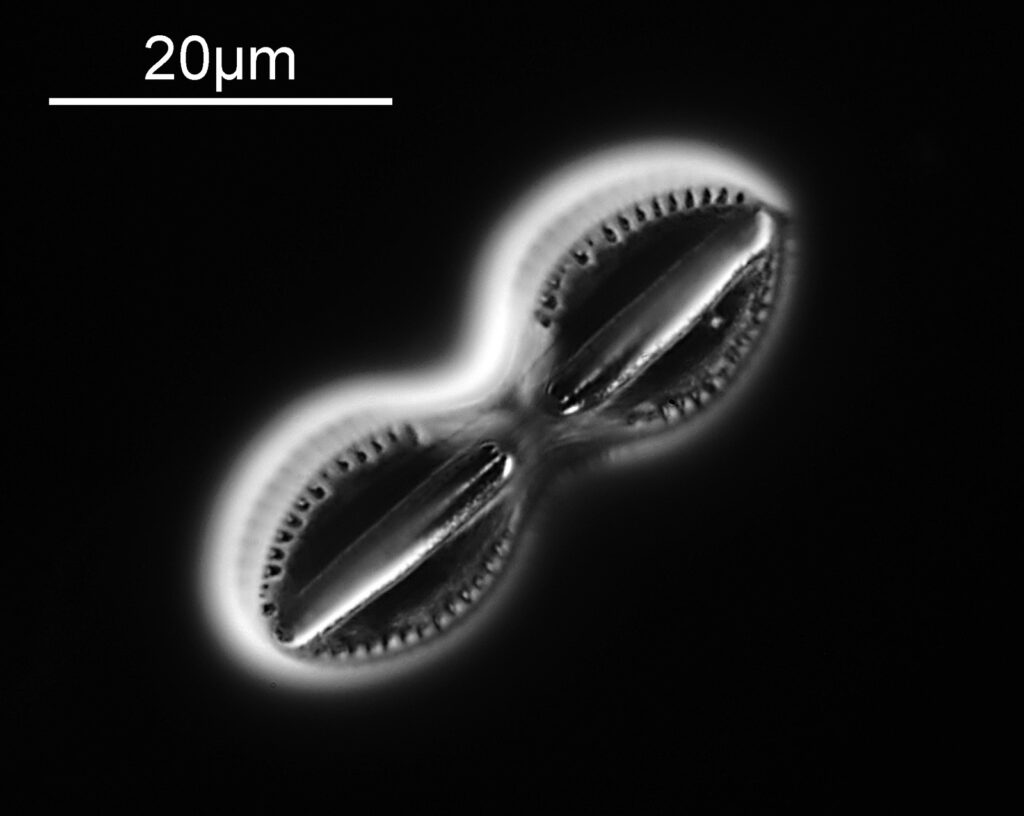

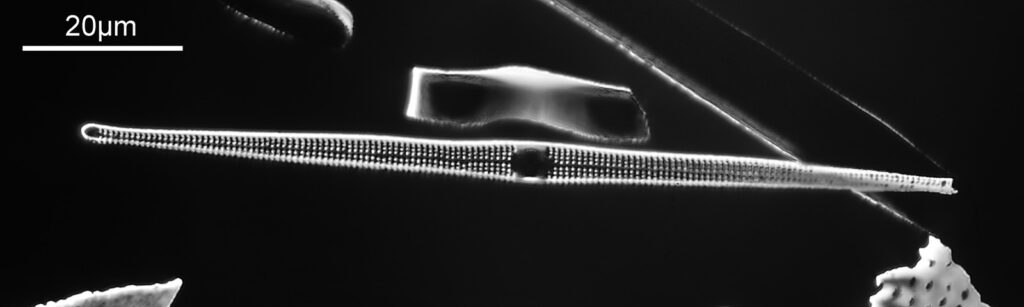

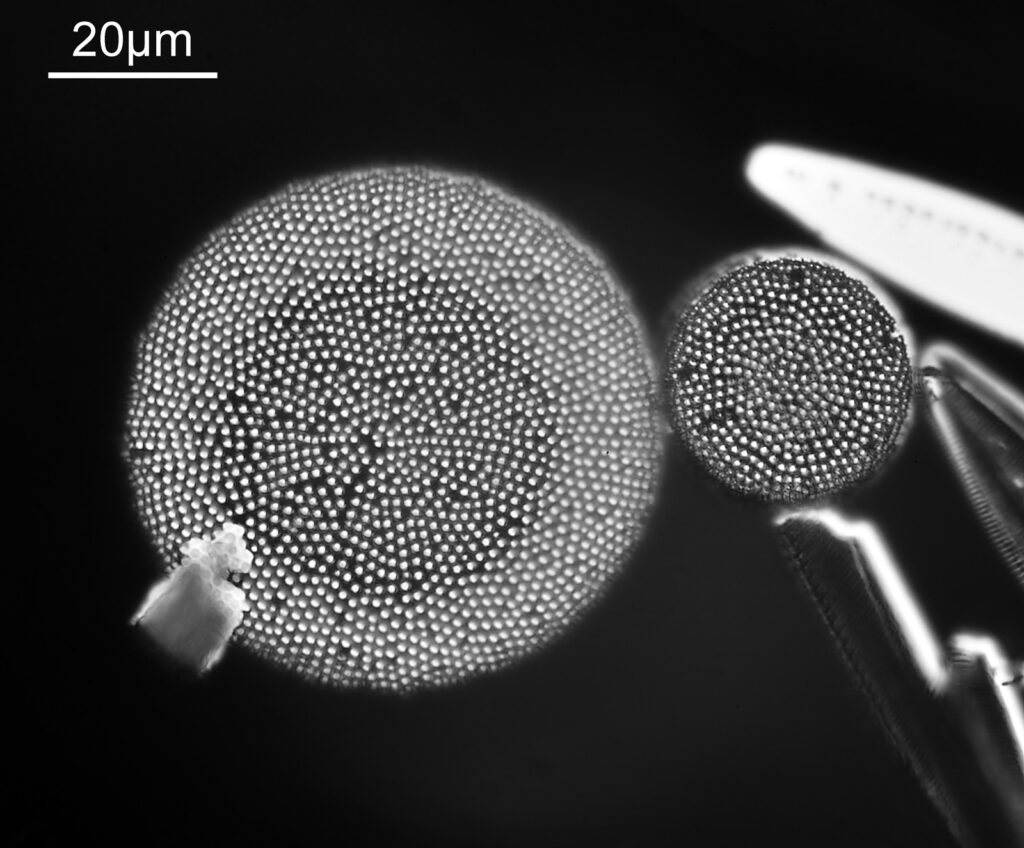

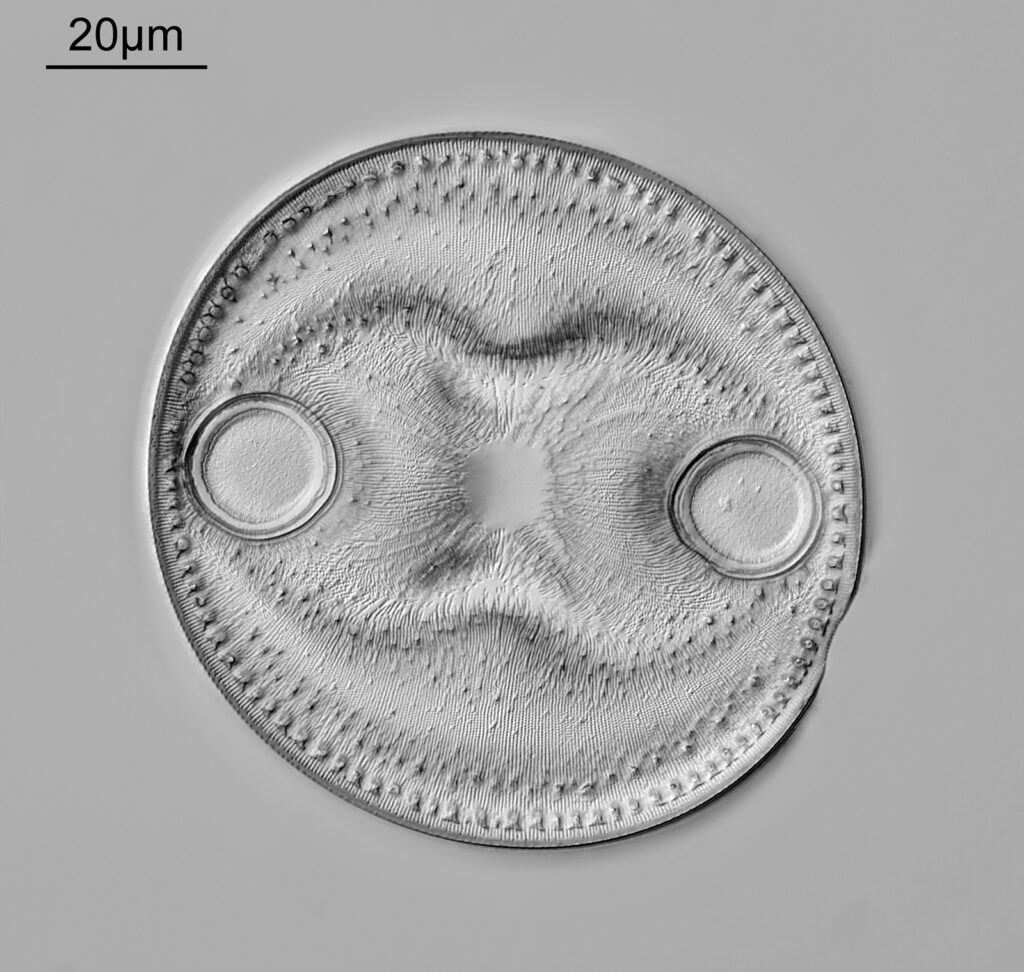

The image above has two diatoms in the centre, a circular one on top of a lens shaped one. This reminds me of an eye looking back at me through the microscope. Next is a tiny one, being only about 20 microns across.

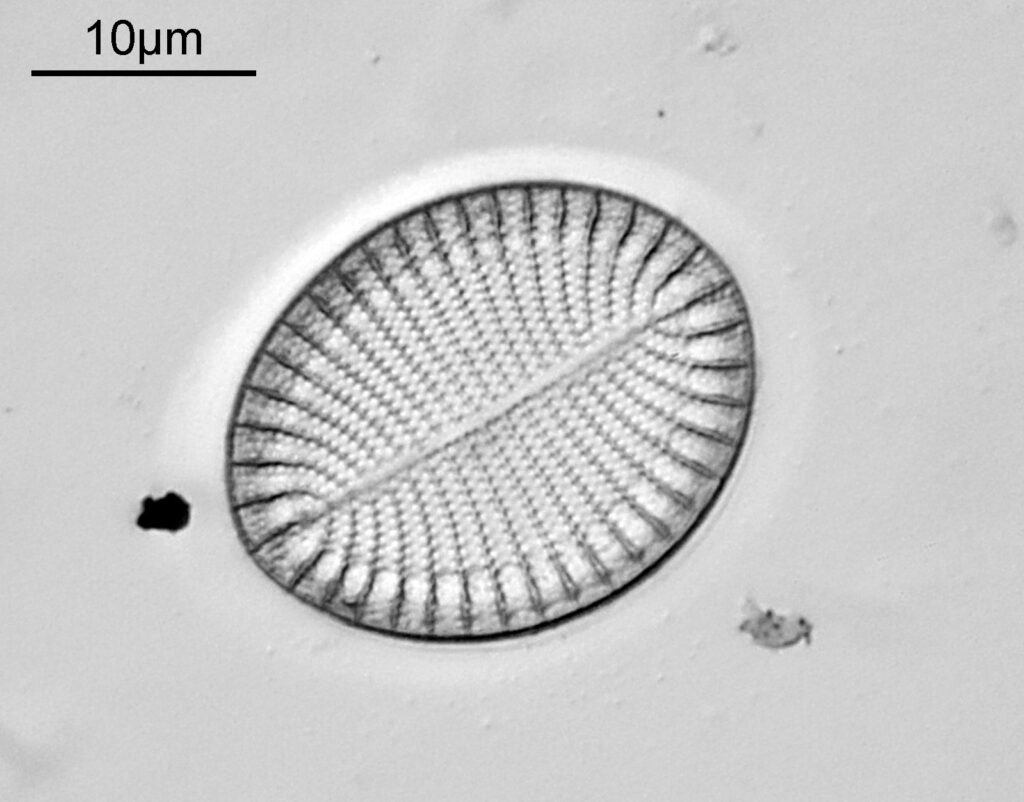

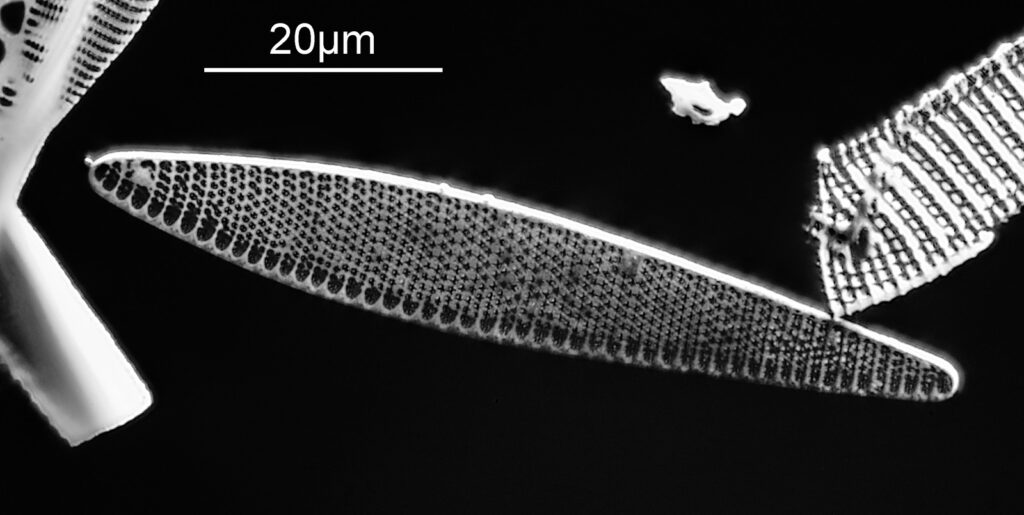

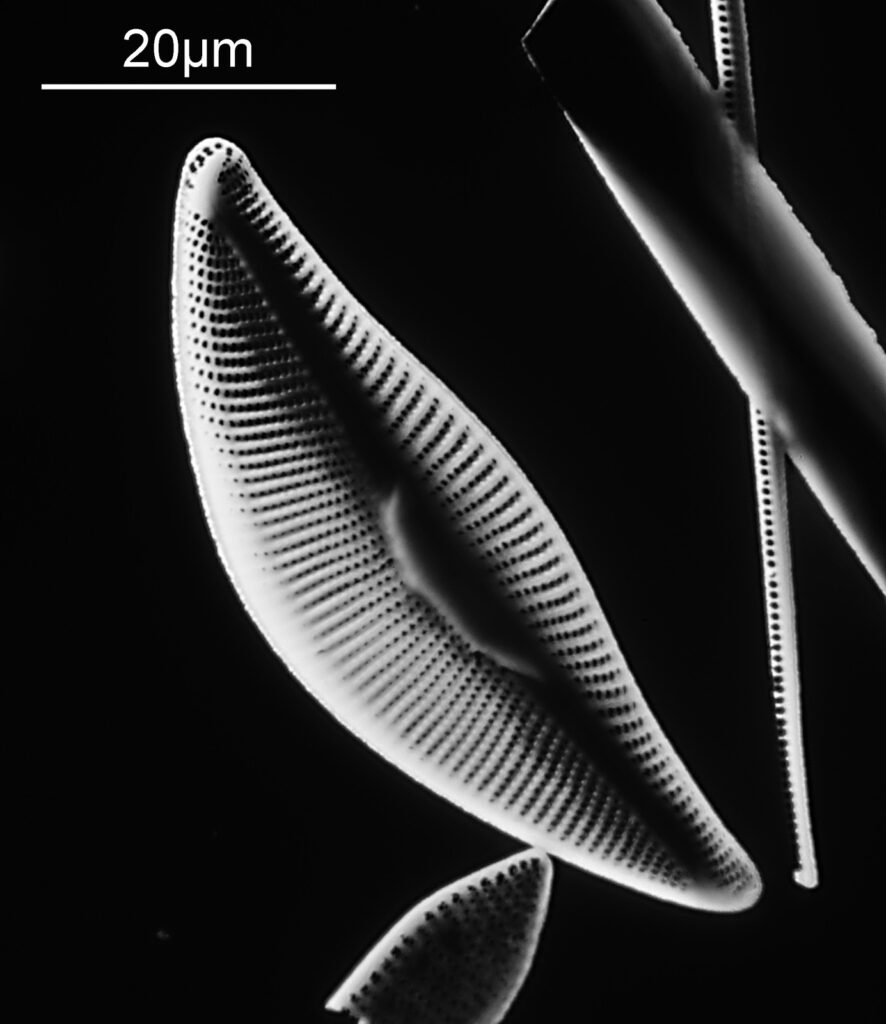

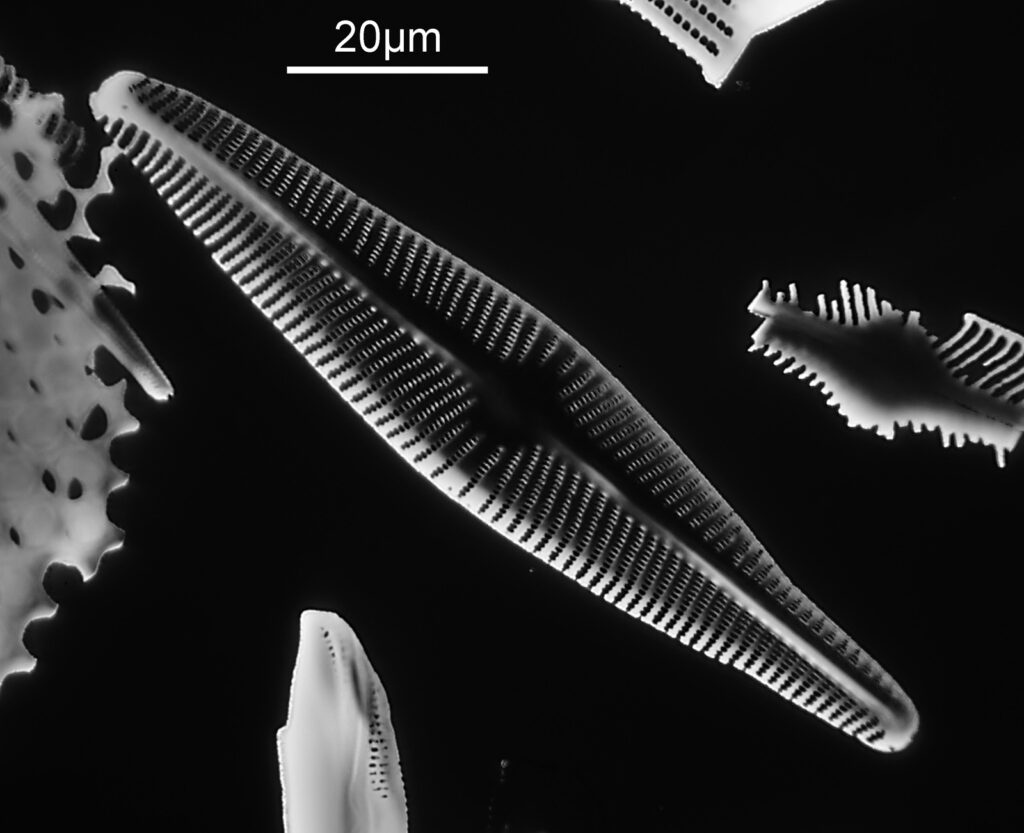

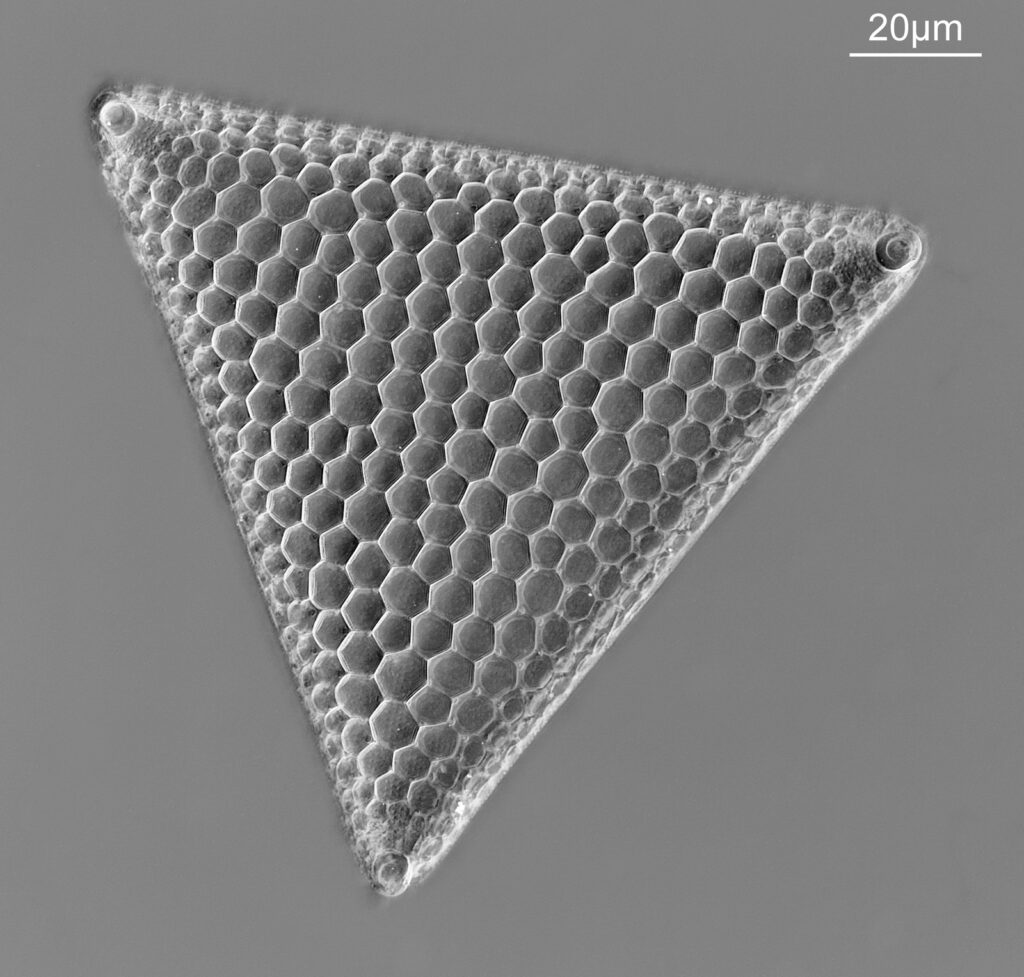

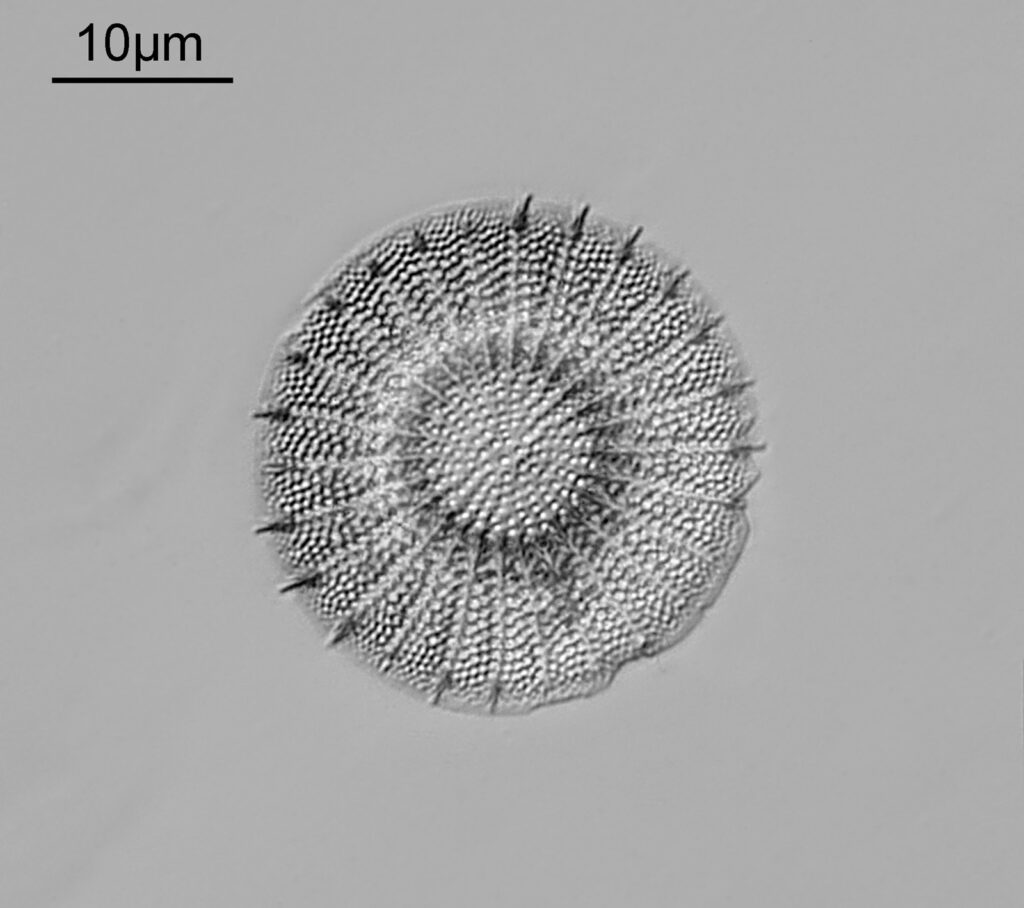

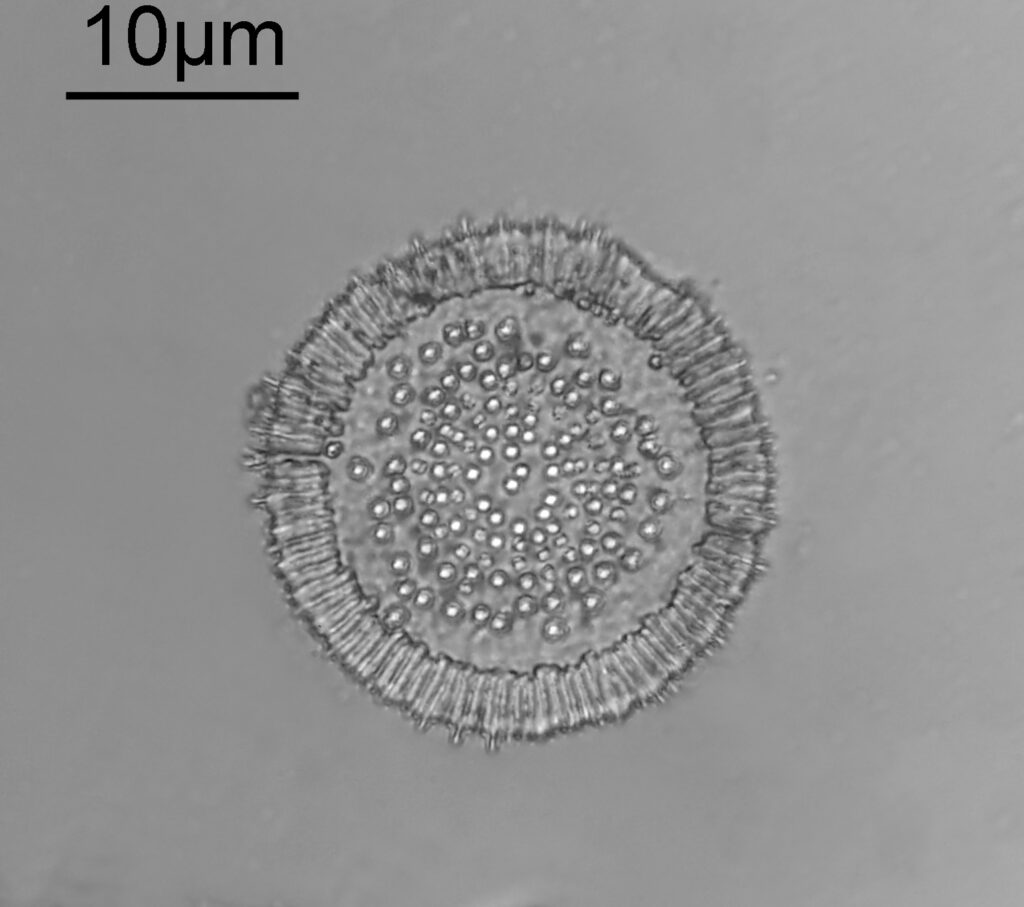

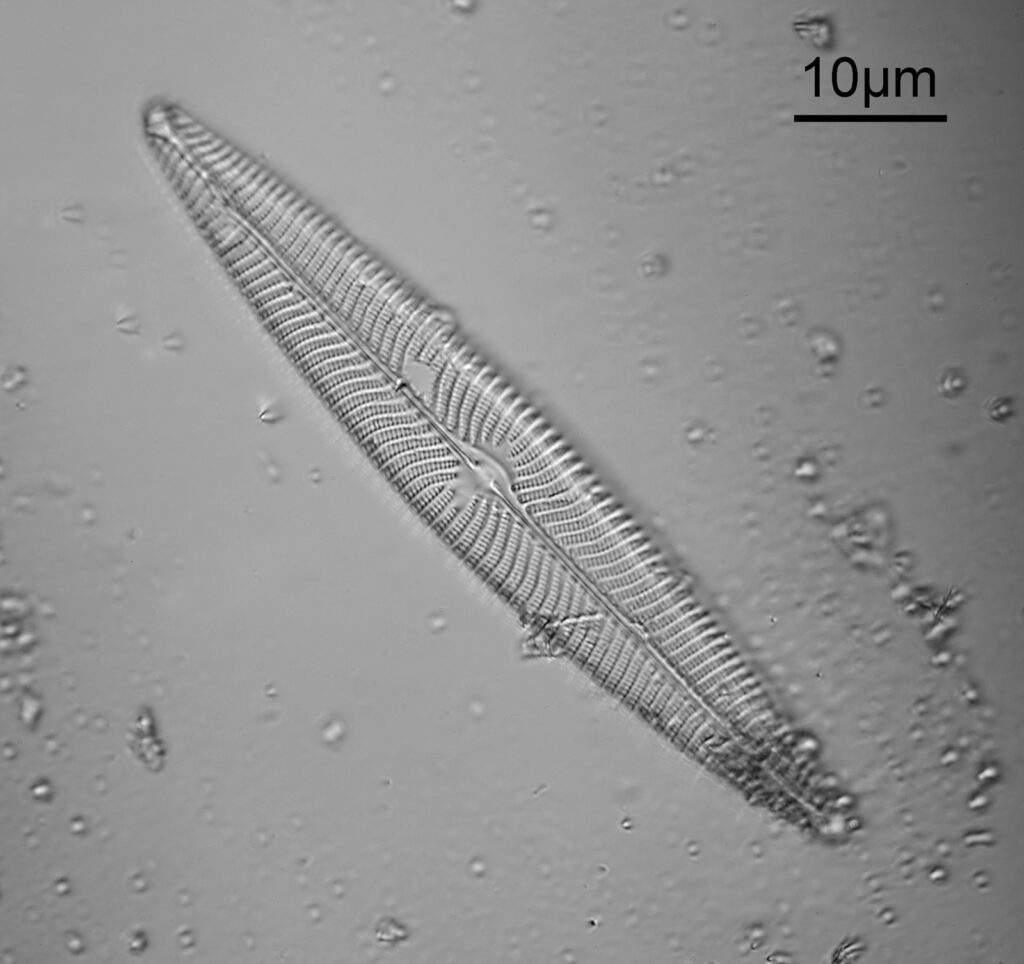

This one was tiny, being only about 20 microns across. Next is I think Navicula radiosa. I was using 365nm UV illumination for this slide, and a 63x Leitz Pl Apo objective with an NA of 1.40. Hence very high resolution.

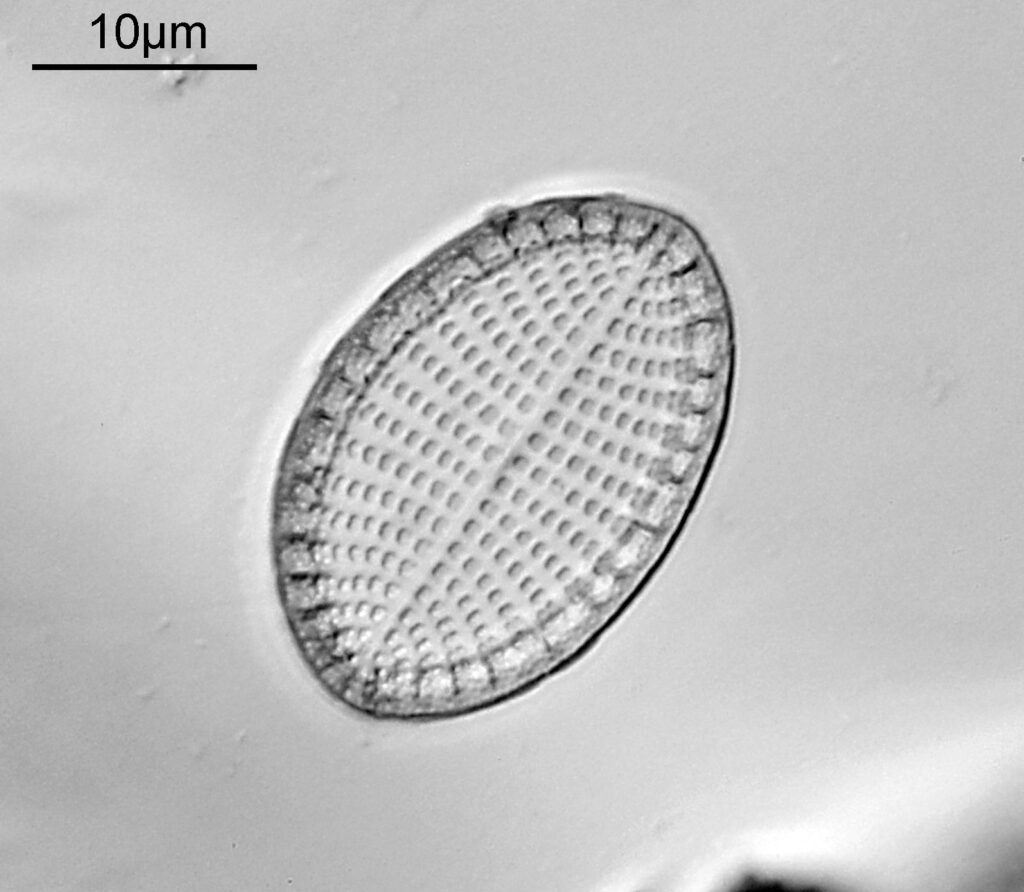

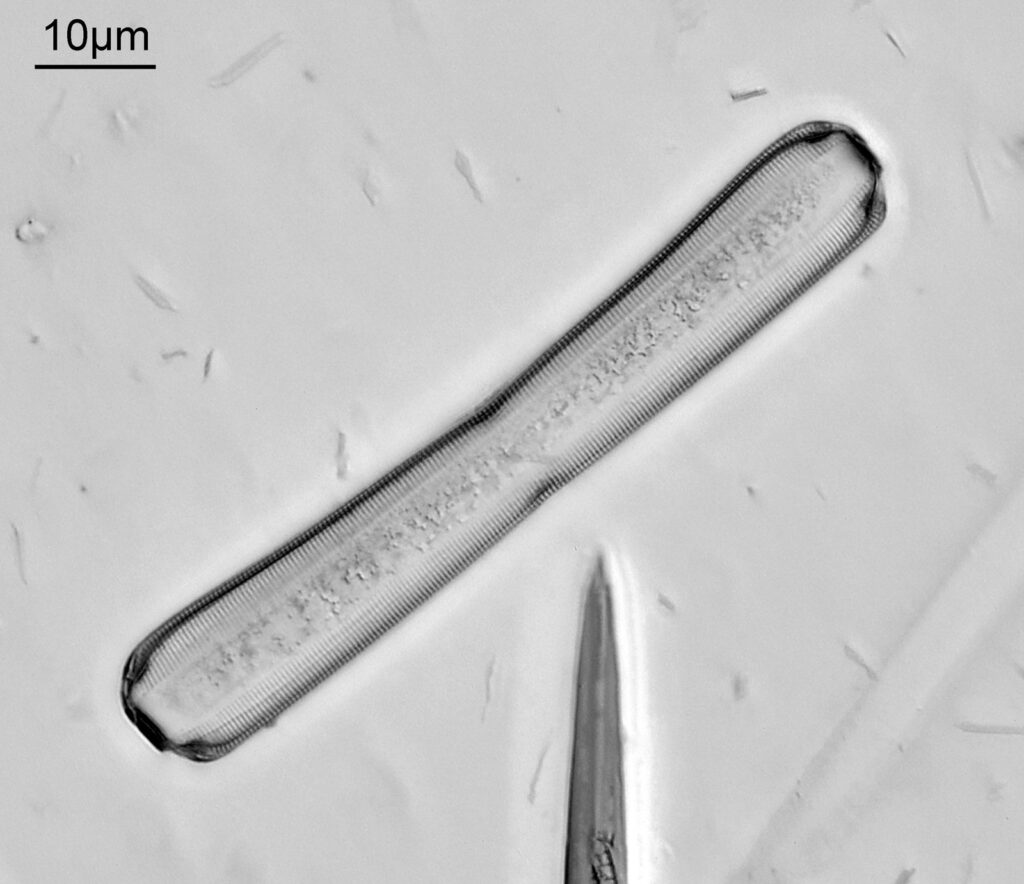

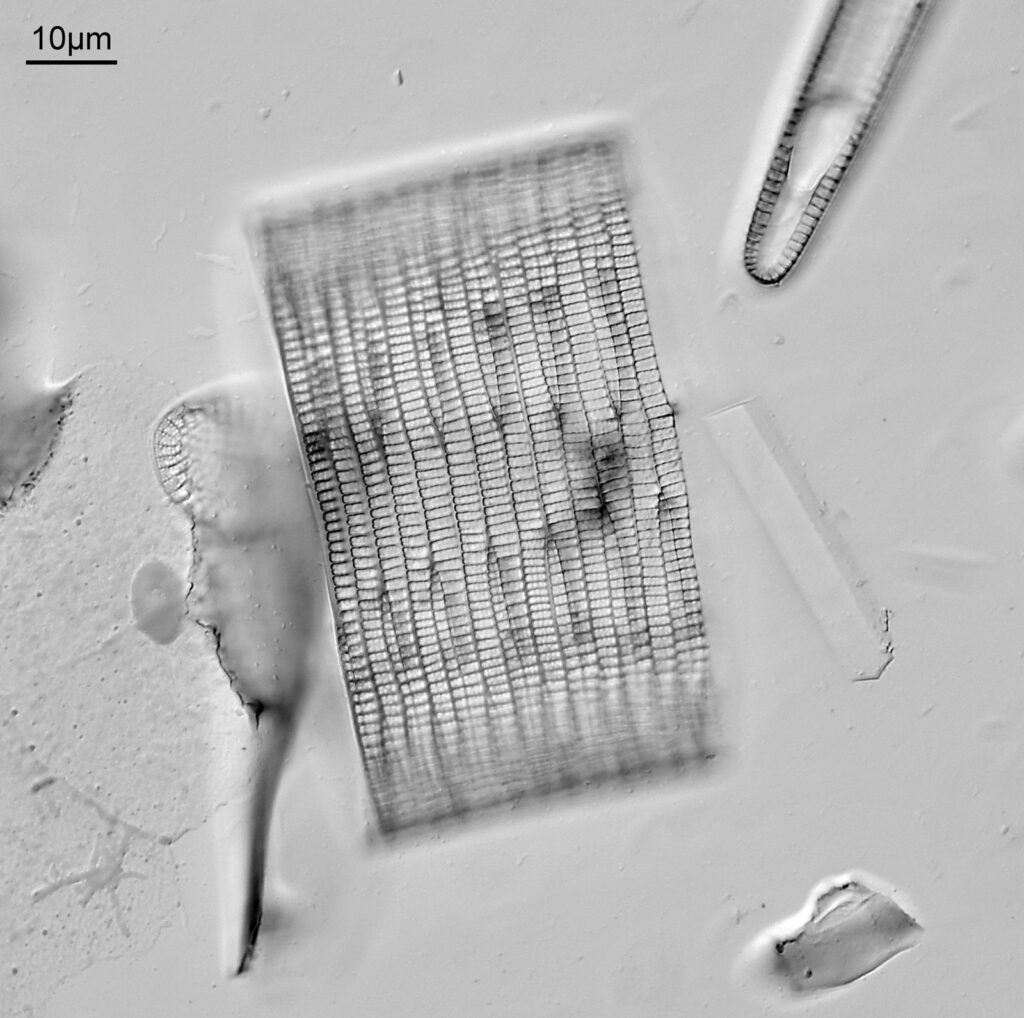

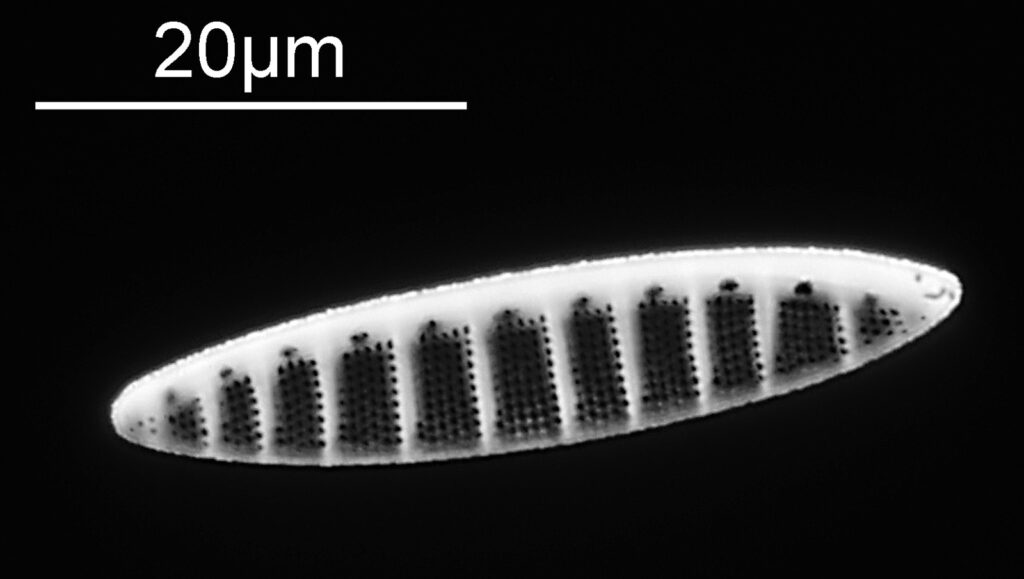

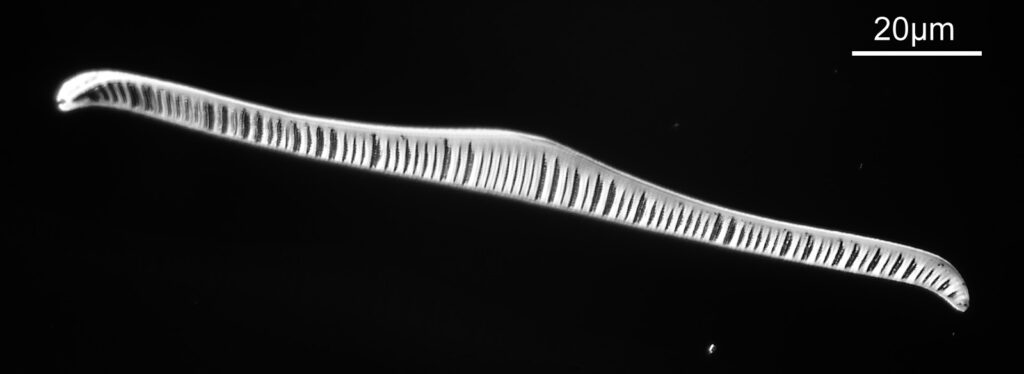

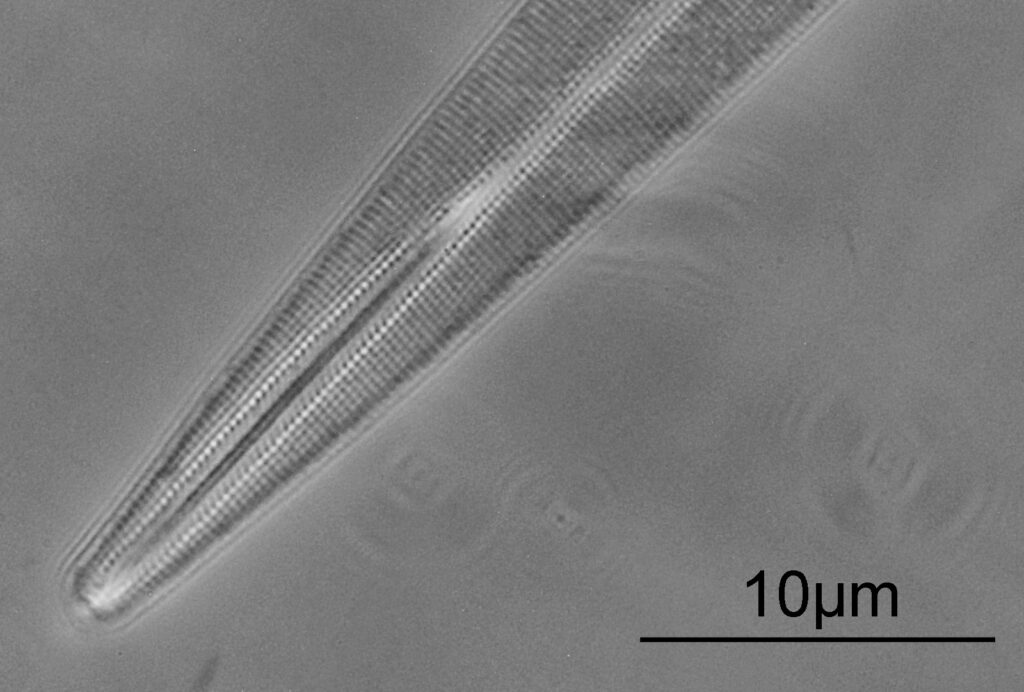

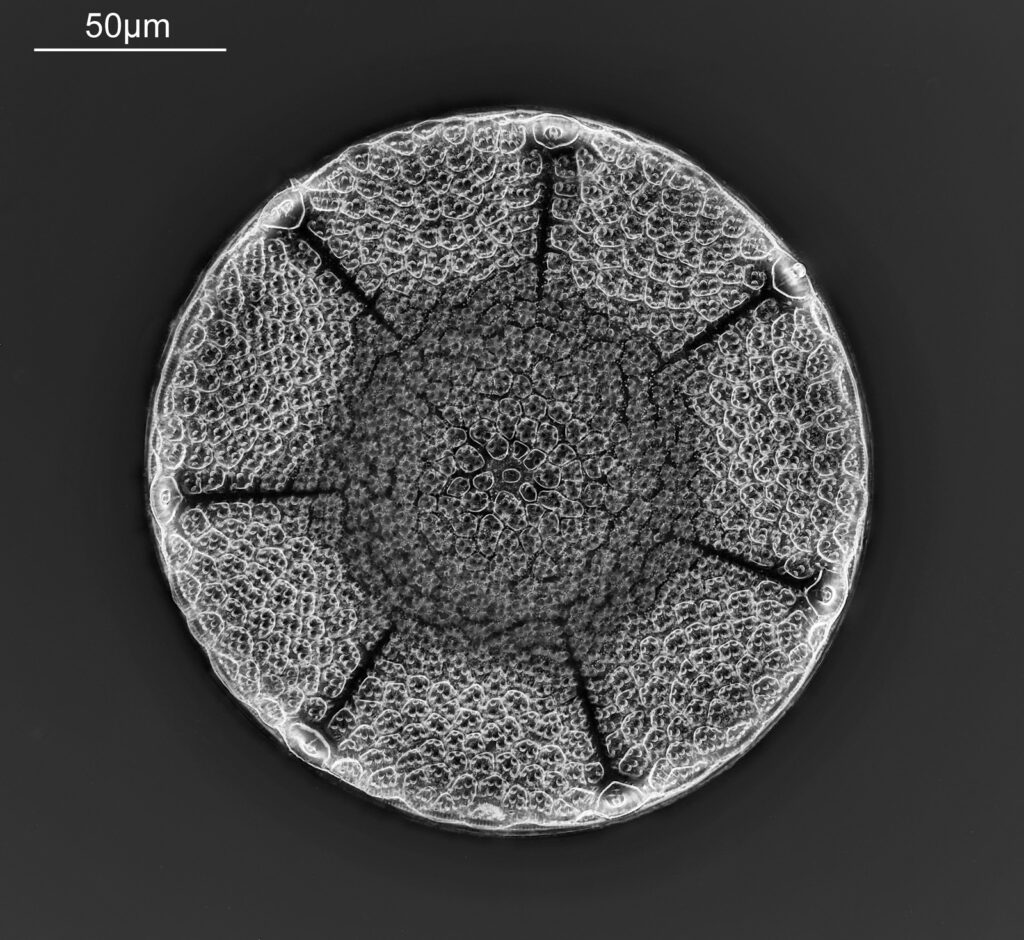

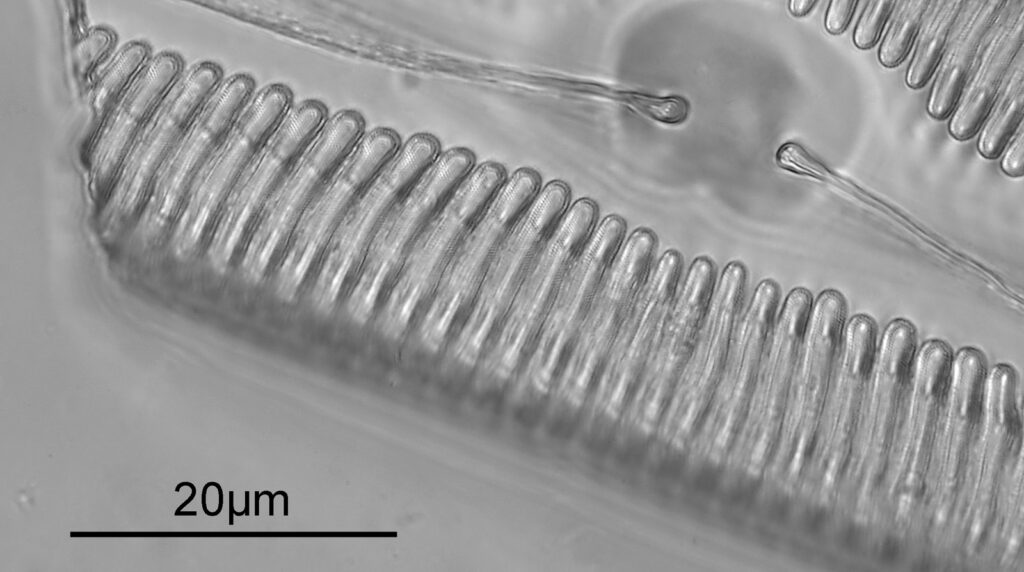

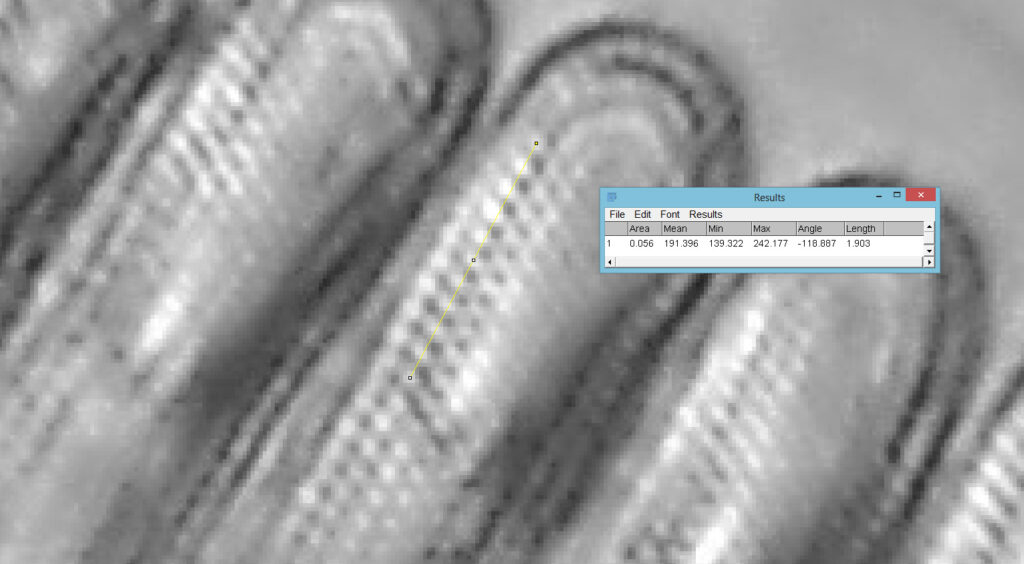

Below is part of a Pinnularia.

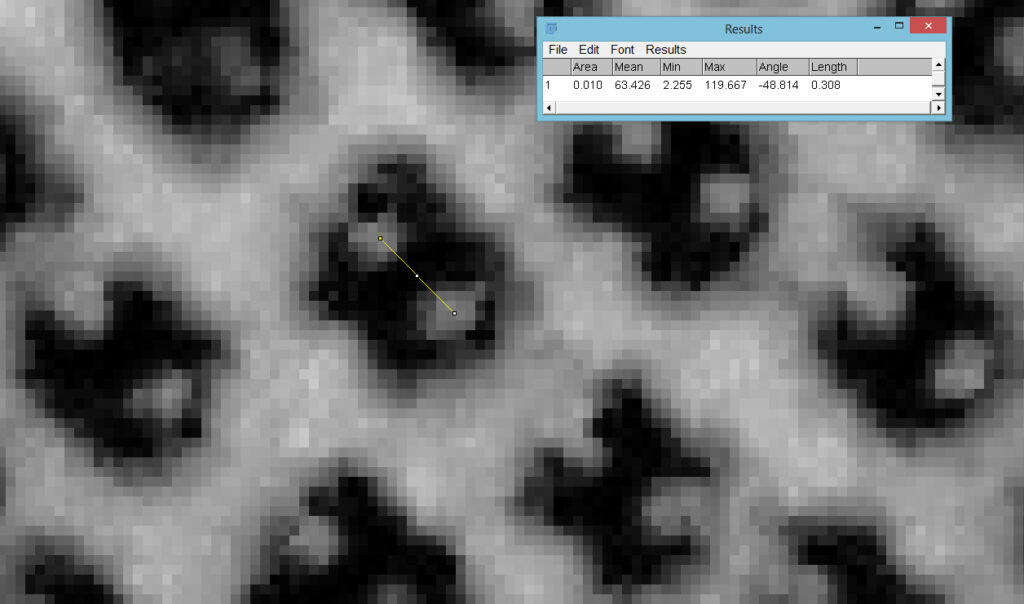

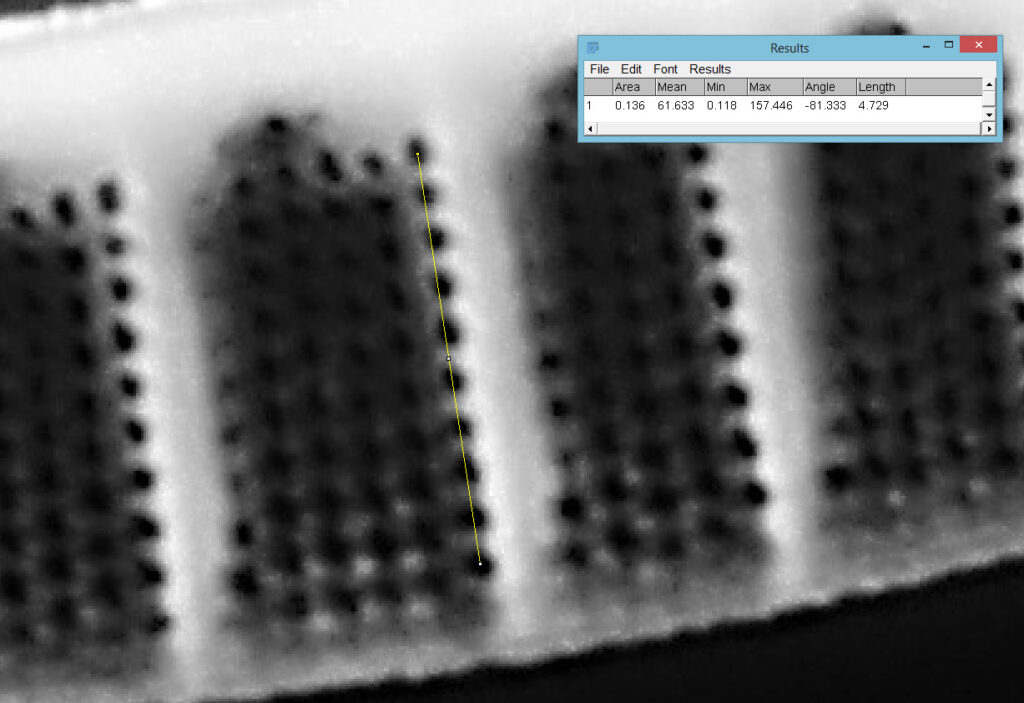

Going in close to this I got the following.

Based on the analysis in ImageJ, the spacing of the poroids here is about 190nm. Theoretical resolution with 365nm light and the NA 1.4 objective is about 130nm so this could well be correct, and it matches with SEM data I have seen for this species.

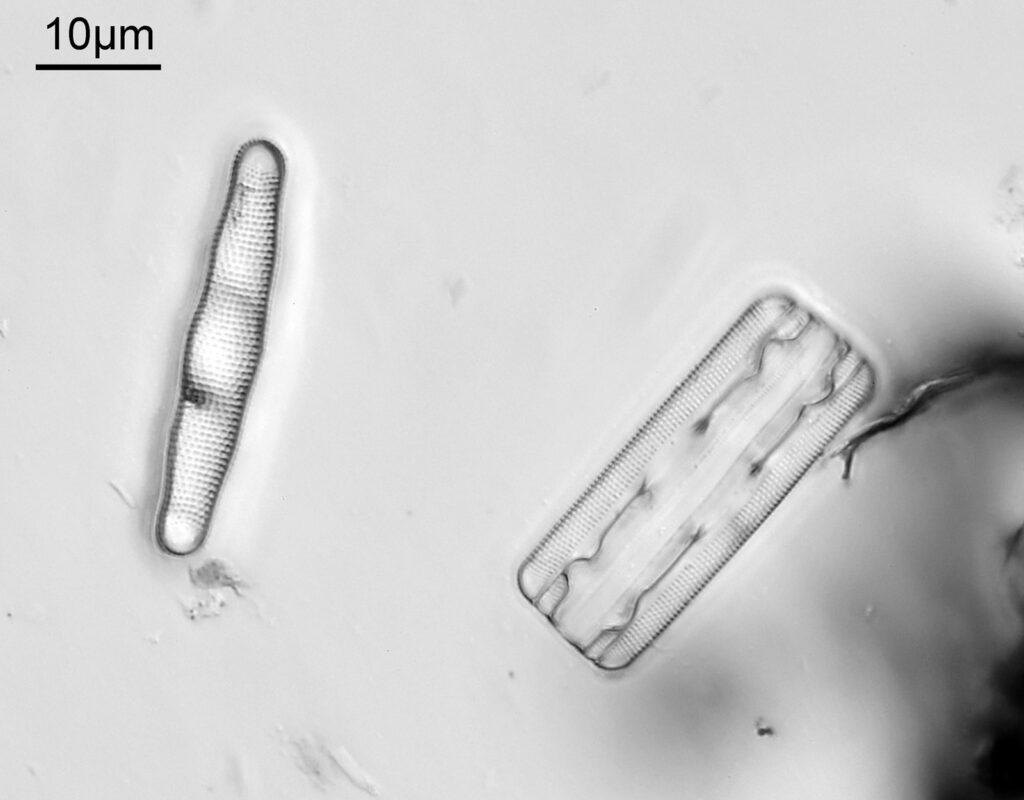

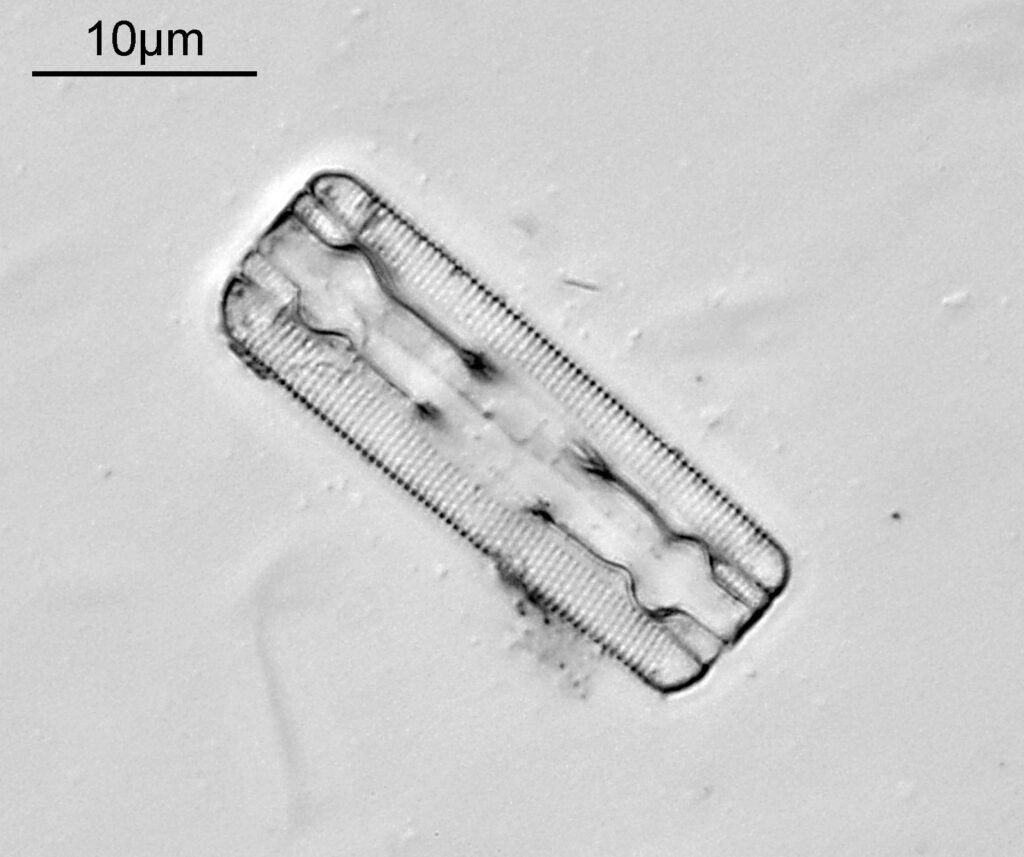

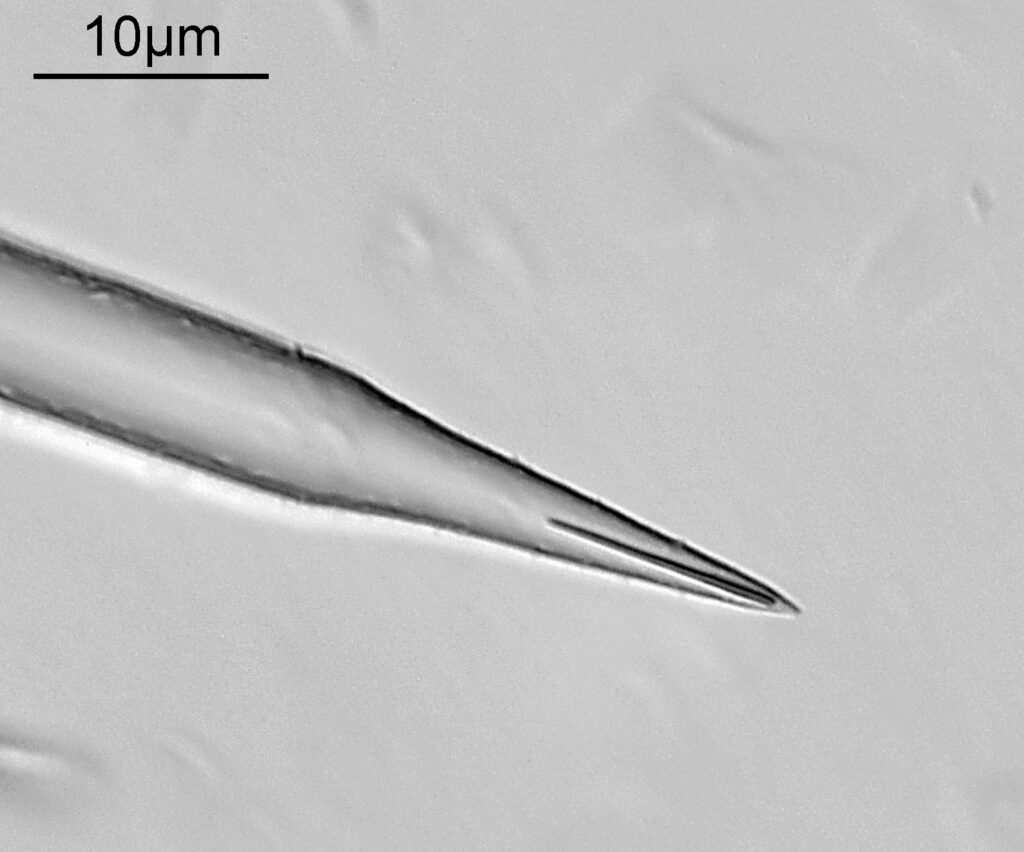

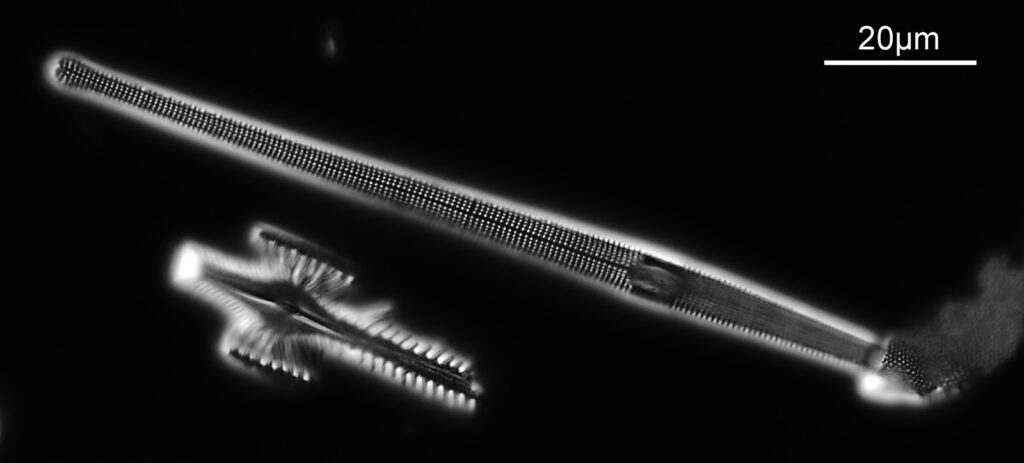

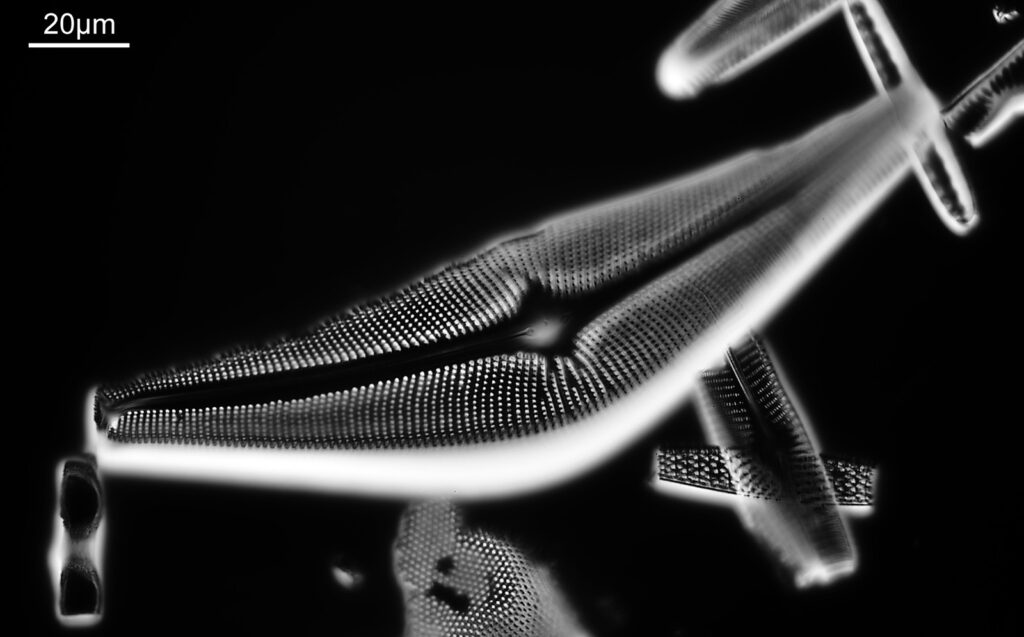

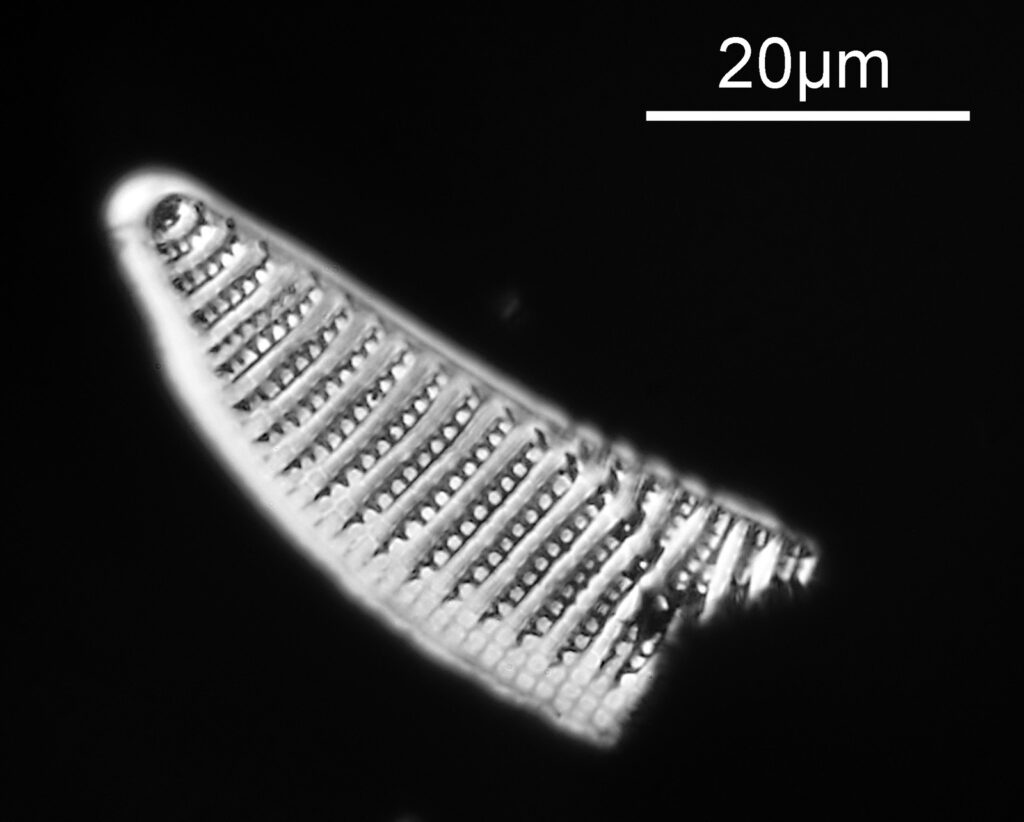

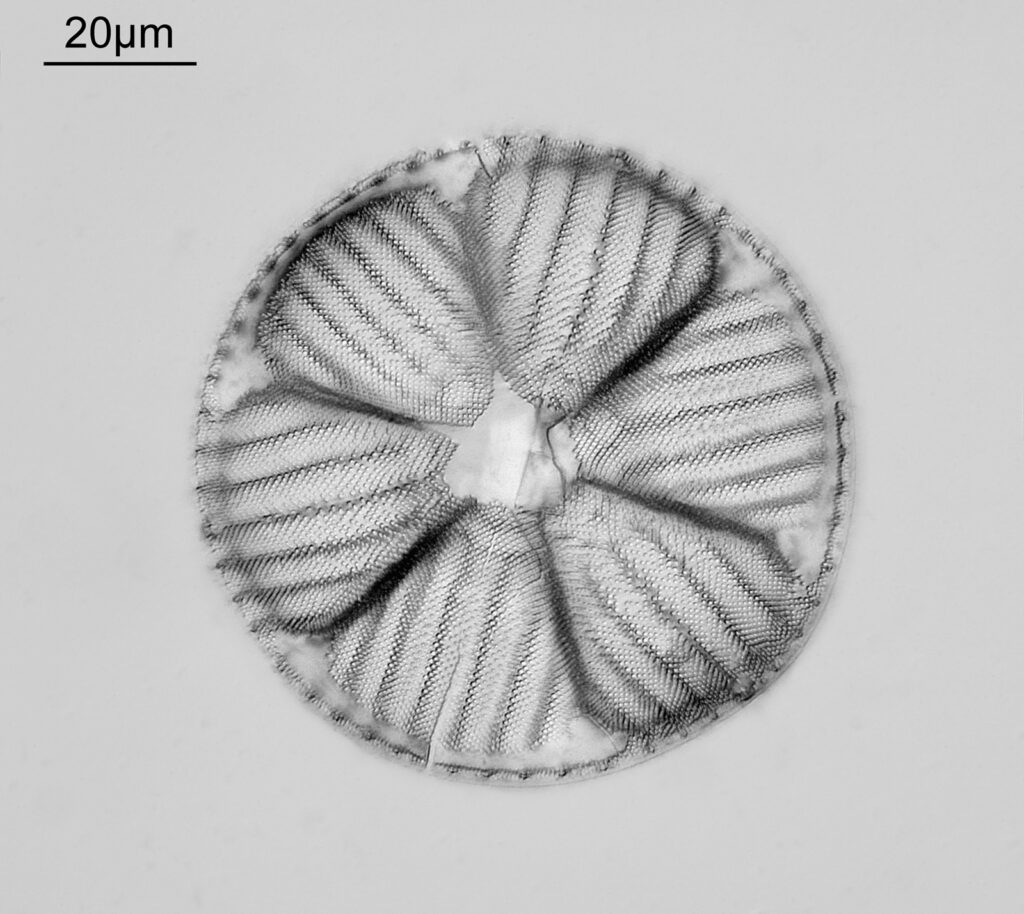

The one below is a Gomphomena.

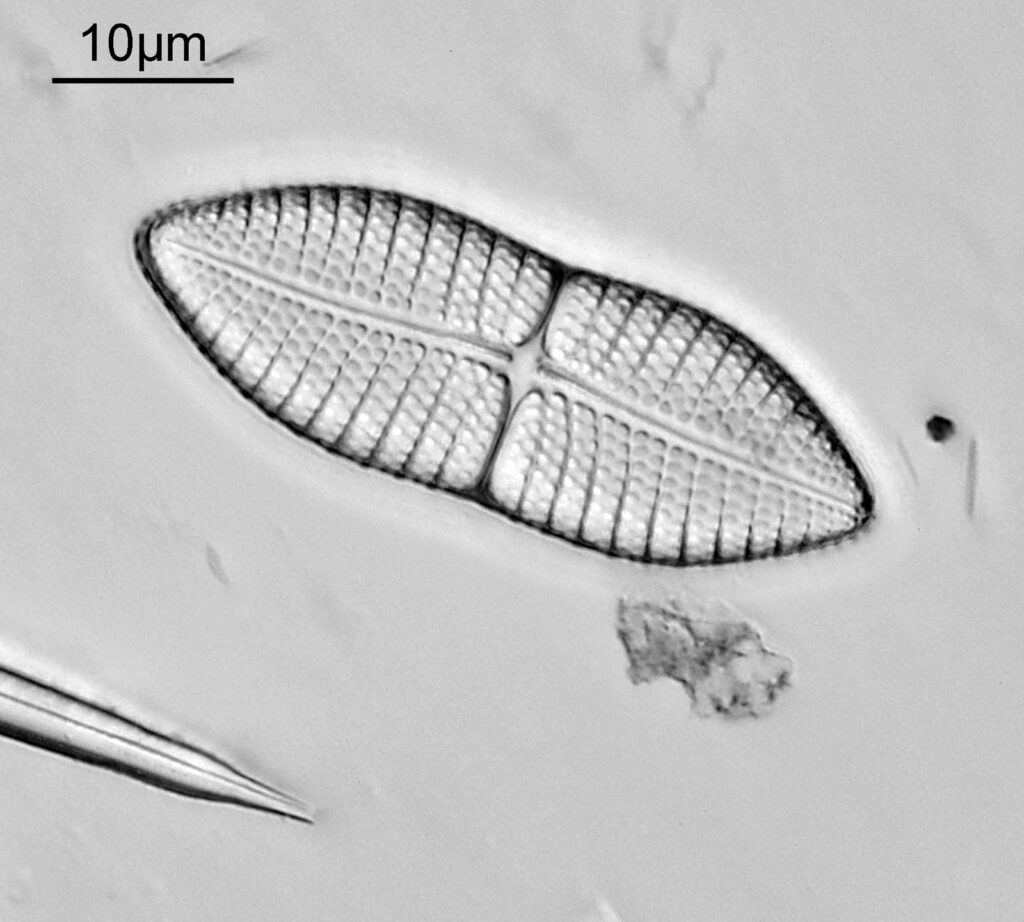

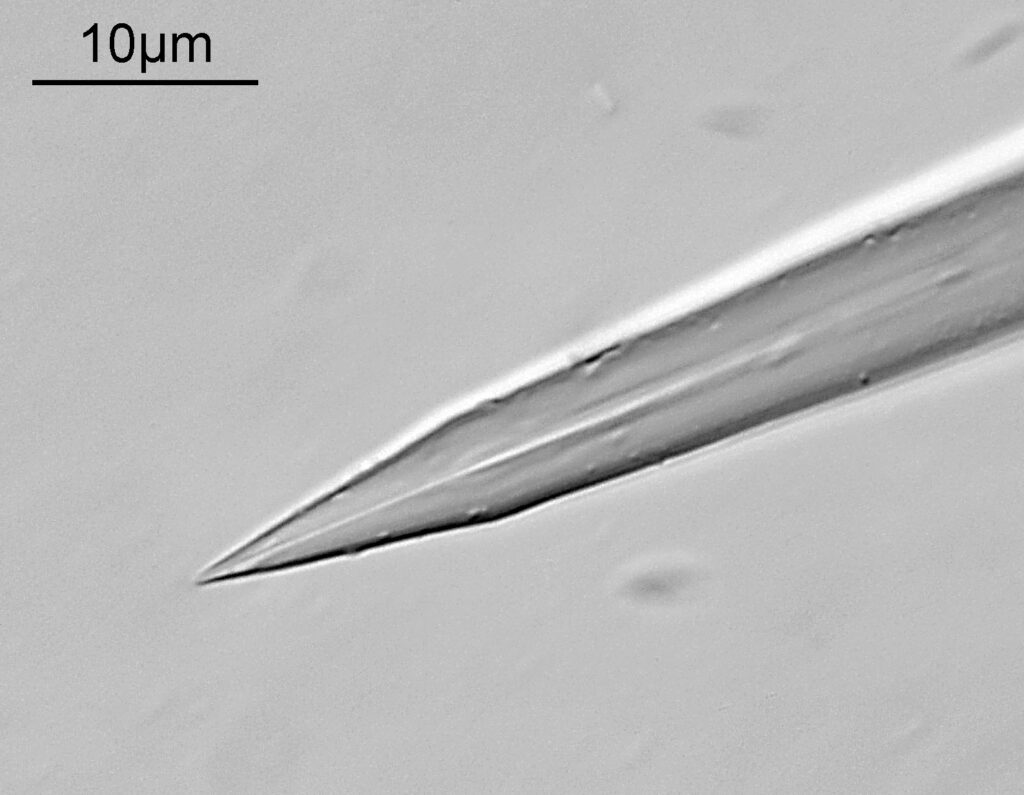

The last one from this slide is a Cymatopleura elliptica.

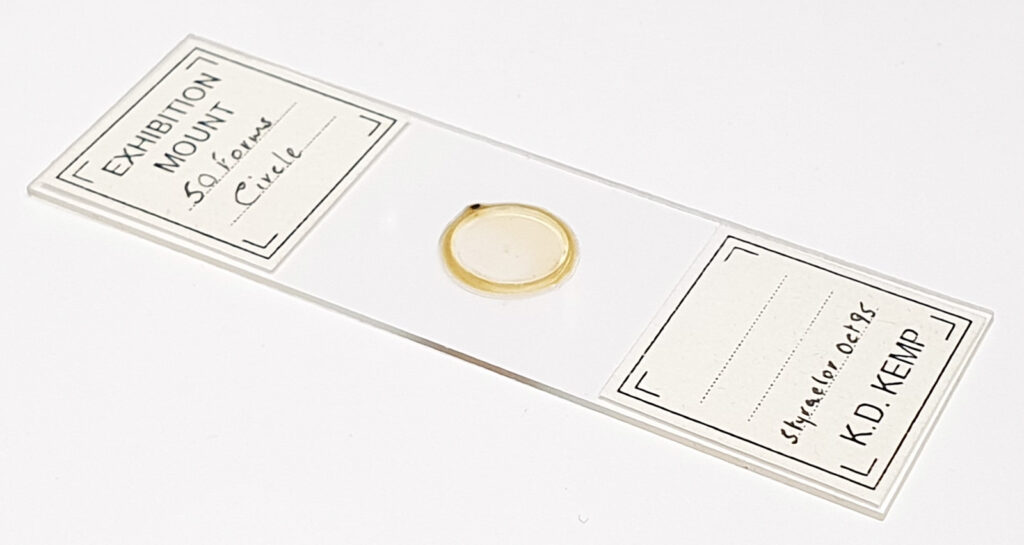

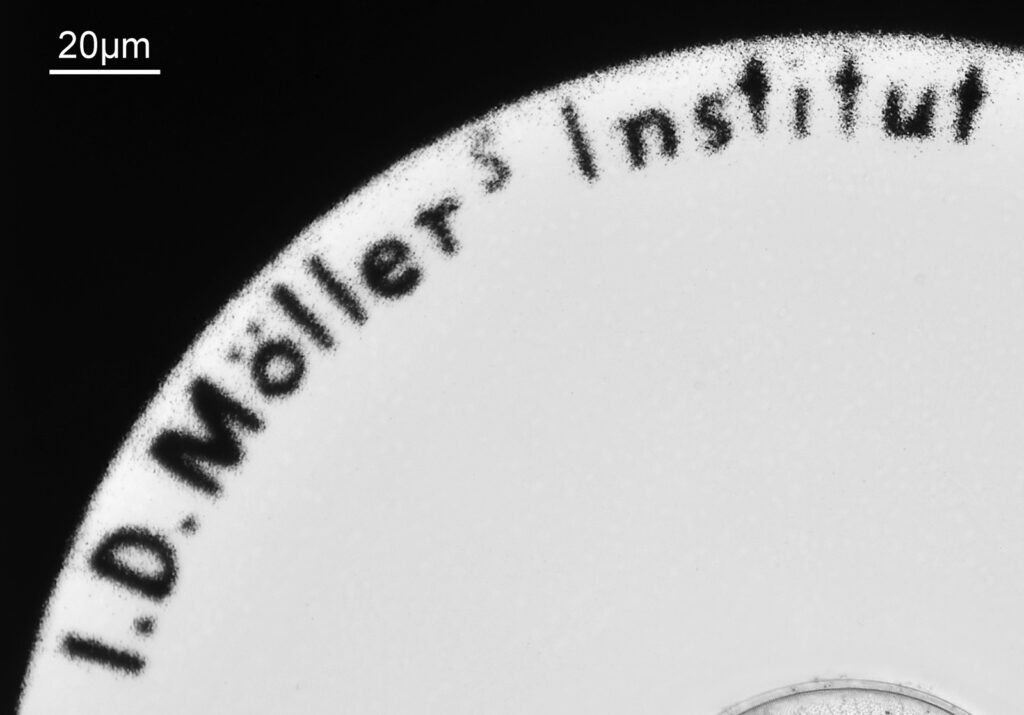

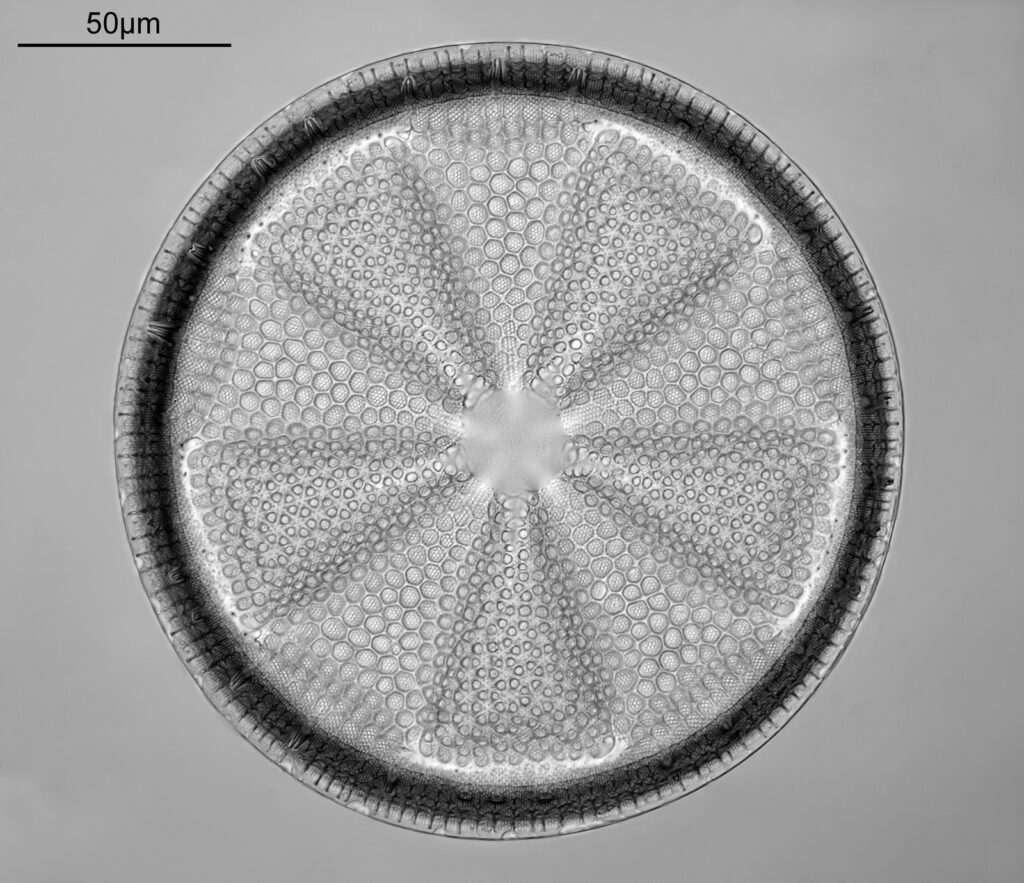

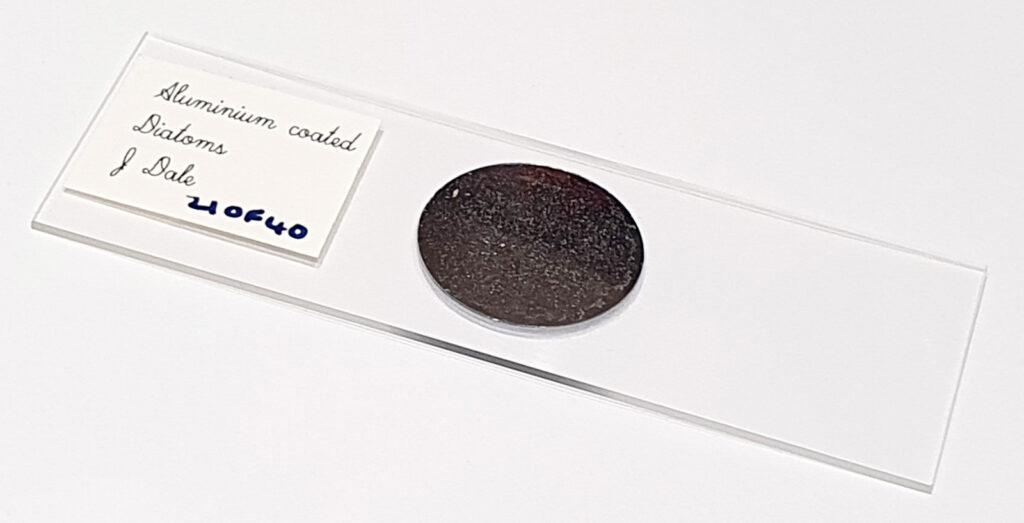

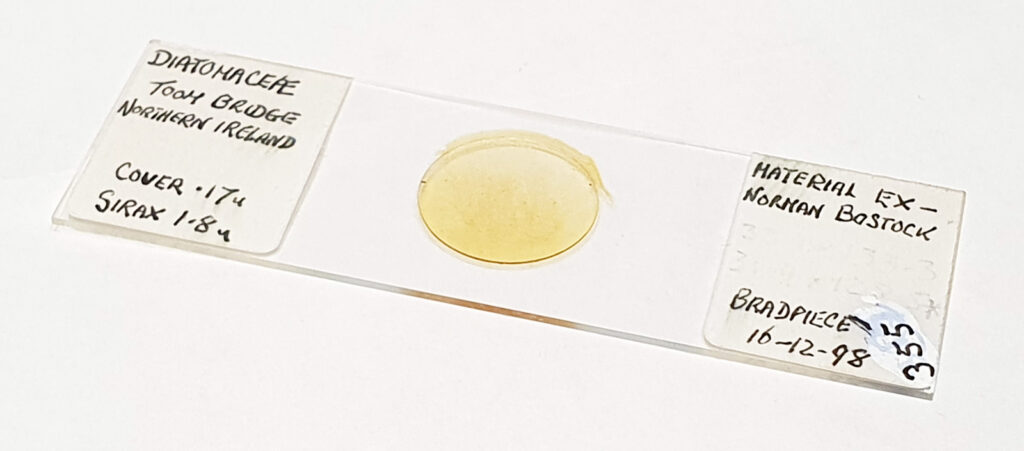

Here’s the slide.

This slide caught my eye as it uses the mountant Sirax, and it mentions the very high refractive index it has (1.8). Sirax seems to be good for UV imaging as it is a high RI mountant which does not block the UV, hence I can get good contrast AND good resolution when using 365nm light. Note yet another spelling on the label – this time Toom Bridge. The images shared here scratched the surface of what was on the slide. I images upwards of a dozen different species from the slide, and that was not all of them. The more I looked the more I saw.

Strew slides are often overlooked in favour of slides with single species on them, but they can provide literally hundreds or thousands of diatoms to image, and are often cheaper than single species slides. This one cost me about £10, and I feel like I got an absolute bargain with it.

As always, thanks for reading and if you’d like to know more about any of my work, I can be reached here.