Picture the scene. Drizzly weather, a long commute into work, and the coffee machine on your floor isn’t working, choosing to blast you with hot steam when you all want is your morning caffeine. A normal Monday morning conversation ensues with your manager. “I have this great little idea, which I’d like to test out”, you say, in your most up-beat tone. “It could solve that problem you were wanting to get to the bottom of, and push the project forward”. Your managers ears pick up, and for a moment you see a glimmer of hope in those glassy eyes looking back at you. “I’d just need to make something to be able to do the testing. Unfortunately we don’t have a workshop on-site any more, so I’d need to go and get someone to make it for me. It could take time and I’d need some money”. The glimmer in the eyes fades, and you go your separate ways, trying to find that mythical working coffee machine……

Ok, slightly melodramatic perhaps, but I’ve noticed a change in the research arena over the last 20 years. There used to be a mentality of ‘make a little, sell a little, learn a lot’, when it came to developing new products, and a similar attitude towards testing – make a prototype quickly and test the idea, and at which point if it works, get funding to do the final experiment. However since then, I’ve noticed a gradual shift away from a practical approach to problem solving, and a greater emphasis on meetings to try and solve problems. Now don’t get me wrong, meetings have their place, but at the end of the day, if you need to solve a technical problem, you need to do some technical work – pie charts and mood boards just don’t cut it. Whereas what used to happen was you’d go off and make something to test the idea, either yourself or with the assistance of the workshop at the site where you worked, the ability for a scientist to do this seems to have been gradually eroded. There are a combination of factors here – increase in the red tape associated with doing research, along with reduction in the number of companies which have their own workshops onsite, are key aspects of it, but the more worrying one which is something I have witnessed first hand is and apparent reduction in practical skills of those working in the labs, along with a greater emphasis on leadership skills training. All well and good, but if everyone leads, you’d better all be pulling in the same direction, and who is actually going to do what needs to be done with the pesky problem which needs solving?

Practical testing is a perishable skill, like many skills – if you don’t push yourself to solve problems, it gets harder and harder to get it back. As part of my research, I often come up against problems for which I need a piece of equipment which I either don’t have, or in some cases doesn’t exist. So I get plenty of chances to flex my practical muscles and try to keep my brain in shape.

As part of my work understanding how cameras interpret colour and light in the UV, I recently had to build a tunable light source, to enable me to measure camera response as a function of wavelength (covered here). When I share this I got a question about how could I show the sensitivity to multiple wavelengths at once and with different light sources? My original setup was no use for that, so I stepped back, did my research and came up with something called a Sparticle board (for instance see here), with a selection of filters covering the wavelength of interest, which you then take a photograph of using the light source of interest to see what light the camera is sensitive to.

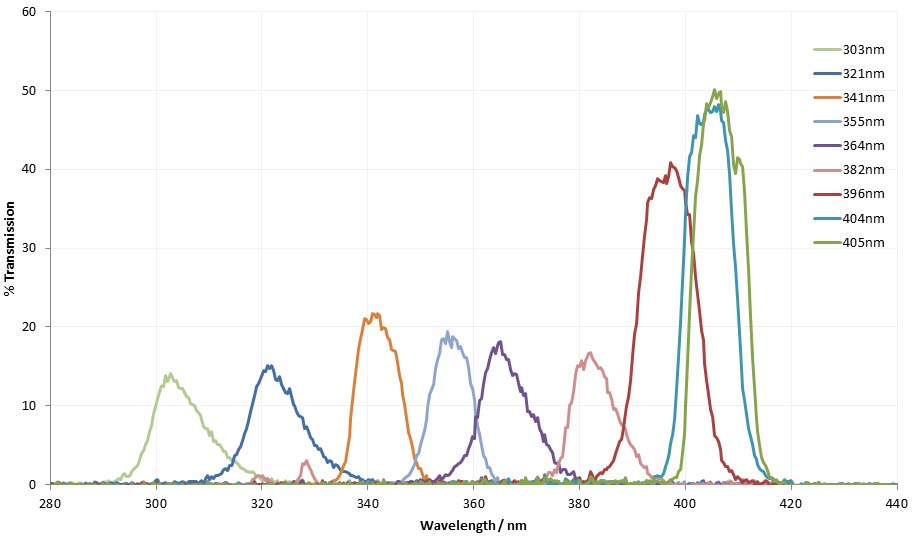

I’m interested in UV imaging, so armed with my fresh cup of coffee, I sourced a set of filters with transmission bands between 300nm and just above 400nm and set about building my own Sparticle. I went with ‘seconds bin specials’ for my filters. For the cost of $15 each as opposed to $150 each, this is the cheap and quick approach to testing a potential solution. The filters sourced from a couple of suppliers in the US, I measured their transmission spectra on my Ocean Optics spectrometer. They gave a nice spread across the UV and just into the visual region;

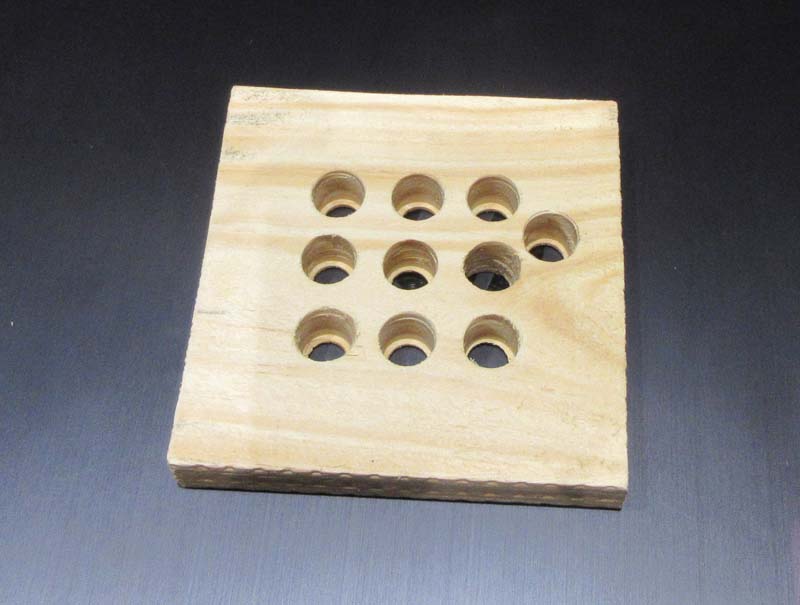

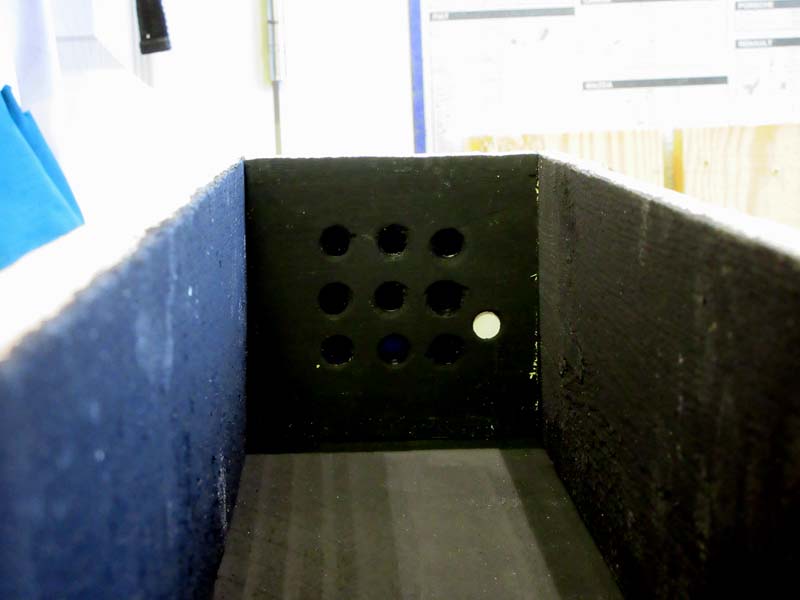

My initial attempt using a nice block of plastic to mount the filters in went horrible wrong – about 30 mins into machining the holes, the drill dug into the plastic and tore it up, ruining it all. Plastic in the recycling bin, I resorted to making the whole thing from wood. It’s amazing what you can make out of old pallets. About 2 hours work, and the same again to paint the inside with Culture Hustle Black 2.0 which is amazing at absorbing light of all wavelengths, and giving a matt black finish to optical housings, and I had a working model. A fun build to be honest, and here is how it looked along the way;

One thing we have in the UK at the moment is a fair bit of sun, so out I went with my new Sparticle filter setup, and my Monochrome UV camera and Multispectral camera and a UV transmitting lens. A simple device really – point the filters at the sky (away from the sun) and the camera goes in the back end of the box and takes a picture of the filters.

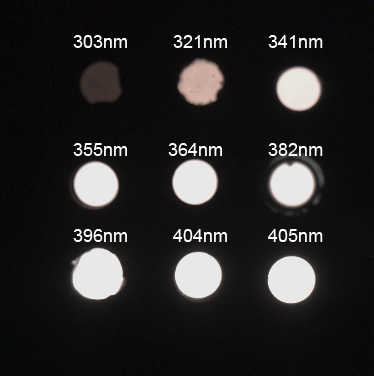

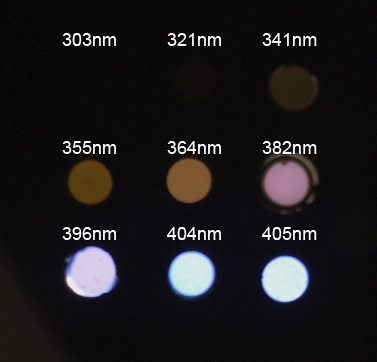

The aim here was to demonstrate the difference between the Monochrome and Multispectral cameras for how far into the UV they can see. Images of the Sparticle filter board with the two cameras on the same settings are shown below. Firstly the Monochrome camera;

And secondly the Multispectral camera (which has the Bayer filter still in place);

For a given set of exposure settings on the camera the Monochrome camera can see further down into the UV than the Multispectral camera, being able to see the light from the sun coming the filters at 321nm and even at 303nm. This is because removing the Bayer filter / microlenses array drastically increases the amount of UV which can reach the sensor. I’ve been able to measure camera spectral response before, but this has allowed me to capture comparative images of multiple wavelengths at the same time in sunlight.

What would the alternative have been here? Time to approach your manager with a lovely question, “I’d like £4000 to have someone make something for me which will take 3 months to so, and I’m not sure will work, but in theory it should. Can In have the money please, and I’ll have the answer for you by Christmas, assuming the group I approach to make this for me are on our Purchase Order system.”. Hmm, this doesn’t sound like a rapid prototyping approach anymore.

And now a call to arms – Scientists put down your highlighter pens and take back the lab – never forget what your strengths are. The ability to look at a problem, formulate a strategy and test your theories, make you able to turn your hand to all aspects of research. Just leave the pie charts and mood boards to someone else……