Building a UV transmission microscope presents some unique challenges above and beyond those for visible light microscopy, especially around the availability of materials for lenses and mirrors in the UVB and C regions. Normal glass absorbs short wavelength UV, and the coatings and adhesives used in making visible light lenses often do too. As discussed in my post here, as I pull together parts for my UV microscope I’ll be sharing my findings on my site, in case others are thinking of trying this out.

Today’s piece is about photoeyepieces. On my Olympus BHB it has a trinocular head to which I can attach a camera. To do this, it requires a photoeyepiece, which slides into the tube on the top of the head. The camera body can then be attached with an adapter tube and images taken without the need for any additional lenses. The Olympus photoeyepiece I have is great for visible light images, but I was concerned about its transmission in the UV, and in fact some early tests showed that to be correct. While looking around on eBay, I came across Lomo UV photoeyepieces from a few different vendors in Russia. Given the Lomo UV objectives show good transmission even at short wavelength UV, I wondered whether their UV photoeyepieces would also be good. I bought a selection of them for about 30USD each and after a 2-3 month wait they arrived. Some of them are corrected for specific objectives (to help correct the abberations in the objectives) and one was just marked as 8x. They are shown below.

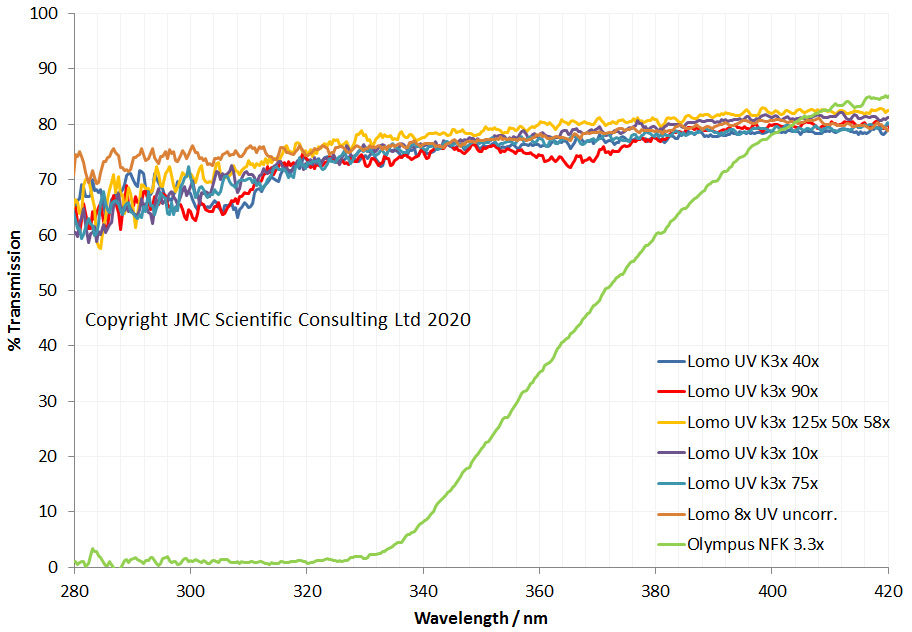

The first thing was to measure their transmission in the UV and compare it to the Olympus one that I have. I did this using the lens transmission system I’ve built (discussed here), and the results are shown below.

Well, the Olympus one really is not good for deep UV – transmission starts dropping at around 400nm, and by 330nm is basically zero – but would be usable at 365nm. The Lomo UV ones however are very different – transmission doesn’t really drop even down at 280nm. I suspect these are quartz and would therefore be good down to around 220nm. Note the Lomo spectra are a bit noiser than the Olympus one, as I used slightly less smoothing during the scans for them. Ok, so that’s the first hurdle crossed – they transmit UV. Next though, is will they make an image on my microscope that I can photograph?

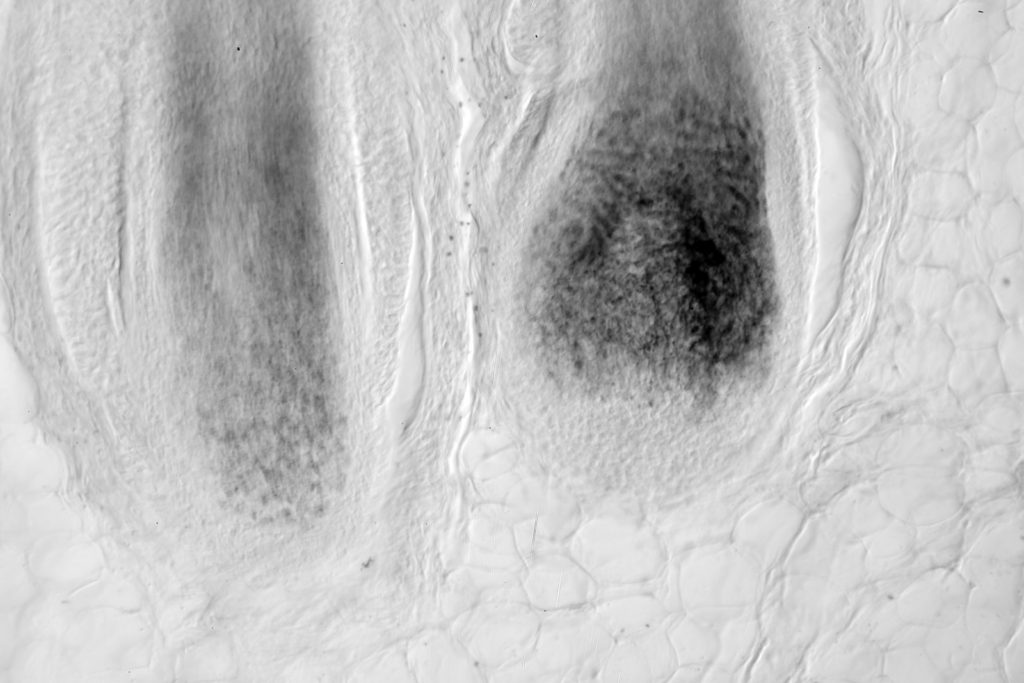

To answer this I used a slide of a section of scalp skin, and set up my monochrome converted Nikon d850 camera on the microscope, along with the Leitz 16x UV objective. I took images of the slide using a normal tungsten light source (this is not a test of UV imaging, just of whether they can create an image, if they work for this they should be fine for UV given the transmission results above) with the different eyepieces. Images are shown as full frame photos. Firstly, the Olympus one.

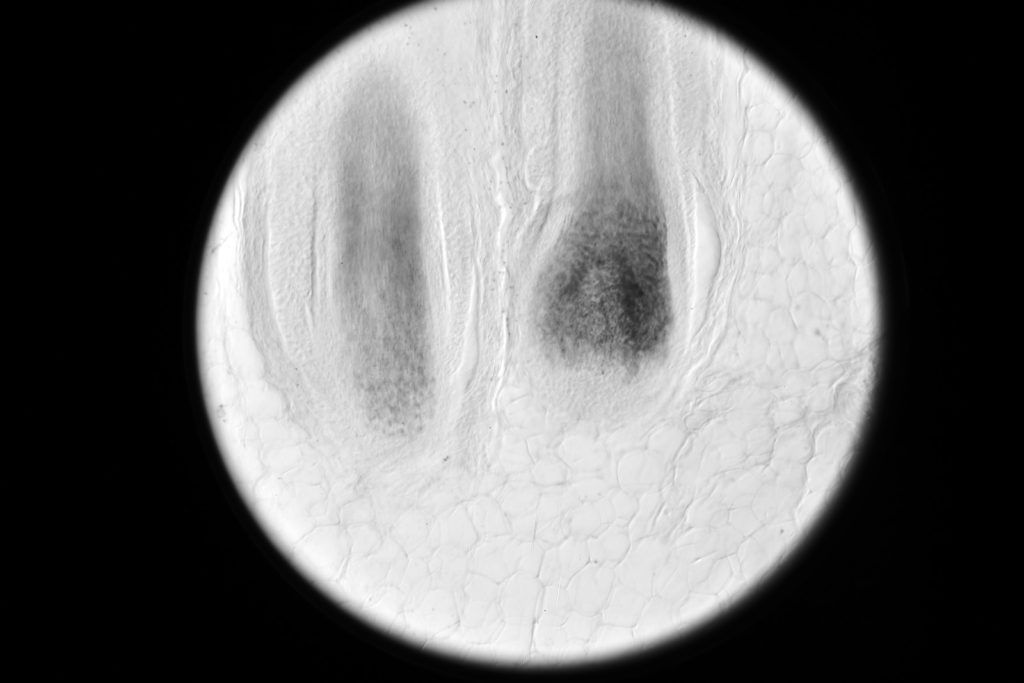

With the Olympus photoeyepiece I get a good image of the hair root bulbs in the scalp which covered the whole frame of the image. With the 3x Lomo UV ones, I got something very different though, and an example image is shown below.

The Lomo 3x photoeyepieces which were corrected for specific objectives did not cover the whole frame of the camera sensor now, although the bit that I could see was a similar field of view to the Olympus. The different Lomo 3x photoeyepieces all behaved similarly but with slight variations in the size of the image circle. On the plus point they all gave usable images. Of course the images would need cropping, but with something like a Nikon d850 with high resolution, that would not be a problem and they would still give usable images.

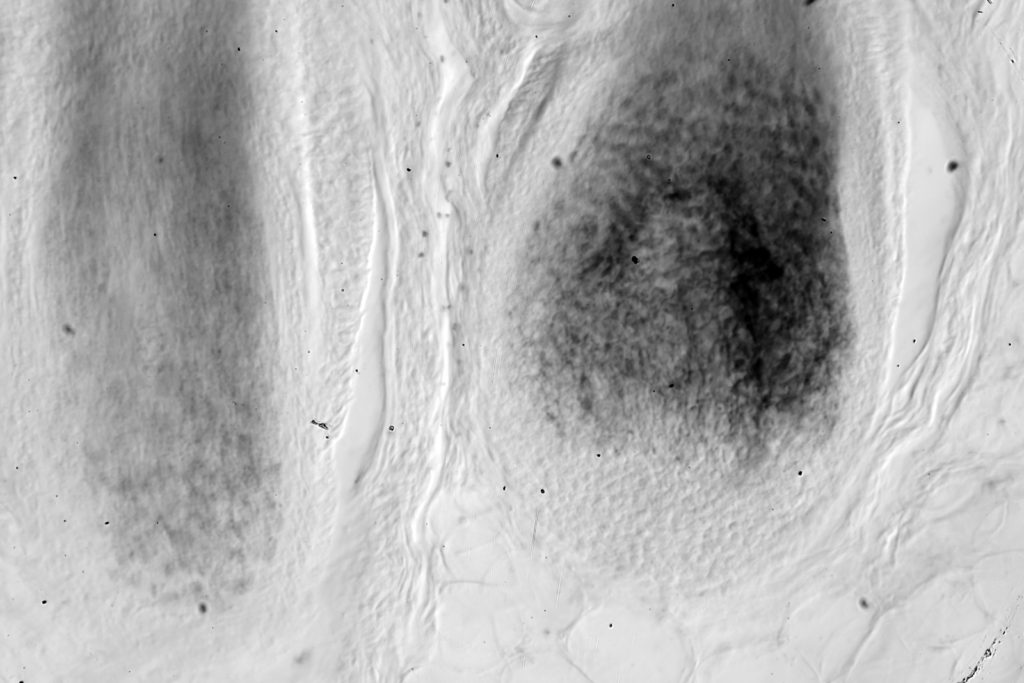

The Lomo 8x eyepiece was different to the others, as shown below.

The Lomo 8x UV photoeyepiece produced an image which covered the sensor of the camera, and was actually only slightly more magnified than the Olympus 3.3x, and will be a good option for use. It is however filthy as can be seen from the dirt in the image, so will need a good clean before using again.

The Lomo UV photoeyepieces have passed their second test – can they produce usable images on my Olympus BHB. Yes, some of them have their issues such as the reduced image size, but given their transmission in the UV this is a small price to pay, and I look forward to trying UV imaging with them.

The development of a UV transmission microscope presents some significant challenges, especially for imaging in the UVB region and below. Knowing a bit about how other manufacturers have solved problems, and being willing to try to adapt other equipment to solve problems is a key part of the research process. Having now identified some UV suitable photoeyepieces for my microscope, I can tick off one of the aspects of the build.

Thanks for reading, and if you want to know more about this or any other aspect of my work, you can reach me on my Contact Me page here.