For those reading my post you’ll be familiar with my Covid-19 project – Project Beater – my Olympus BHB microscope rebuild, and a chance to learn a new imaging skill. As always when playing with new imaging equipment, it quickly turns into a ‘what can I buy for it?’ situation. Reminds me of when in owned a VW Corrado G60, when I spent most of my time (and money) on improving, tuning and generally modifying it. Ah, that was a fun car, and perhaps was my original Project Beater….

Anyway, I digress, and back to the microscope. How you use lighting has a huge impact on the type of imaging you can do with a microscope, and the images you can produce. Bright field imaging, where the sample is illuminated by transmitted light (i.e., illuminated from below and observed from above) white light, and the contrast in the sample is caused by attenuation of the transmitted light in dense areas of the sample. Bright-field microscopy is the simplest techniques used for illumination of samples in optical microscopes. The appearance of a bright-field microscopy image is a dark sample on a bright background. However, this does not always give good contrast between the subject and the background, and there are a host of illumination techniques which can be used for different samples to make them clearer to image.

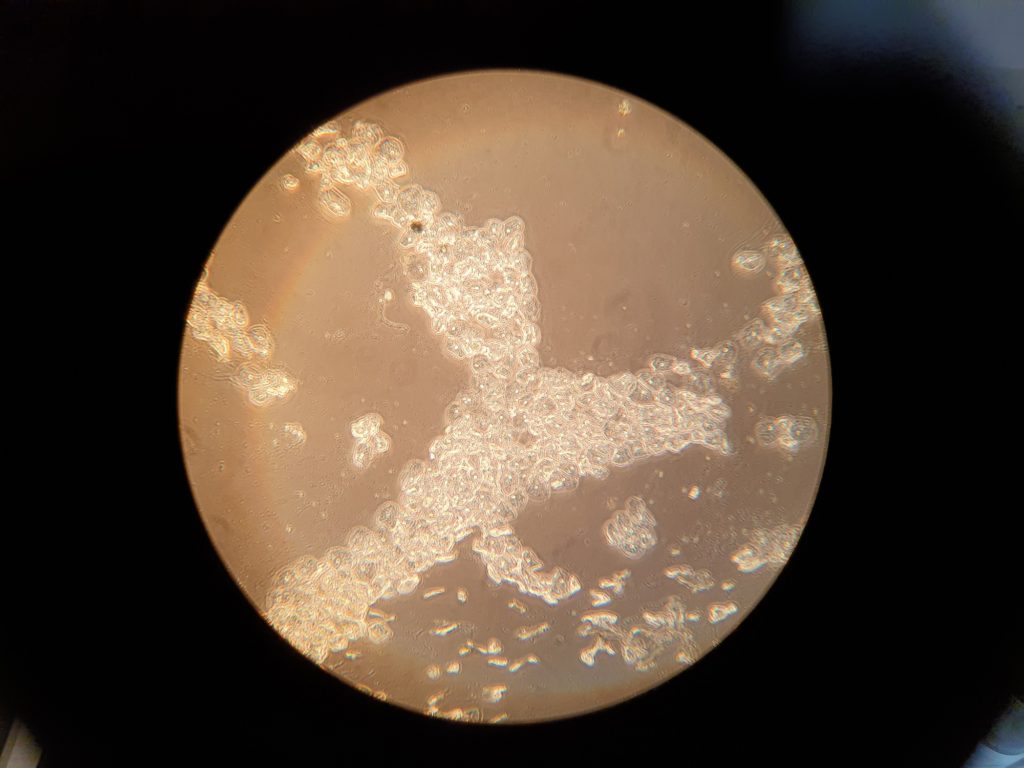

One such approach is called Phase Contrast imaging. I’m not going to give a detailed review of how this works, as there are plenty of those online. It’s a very useful technique for imaging live cells, as it improves contrast without staining. To demonstrate this, below are two images of cells from my cheek collected with a quick buccal swab, taken with a 10x Phase contrast objective, through the microscope eyepiece (100x overall magnification). Firstly, the normal bright field image.

The cells are just about visible, but with very low contrast against the background. And secondly, a phase contrast image of the same field of view.

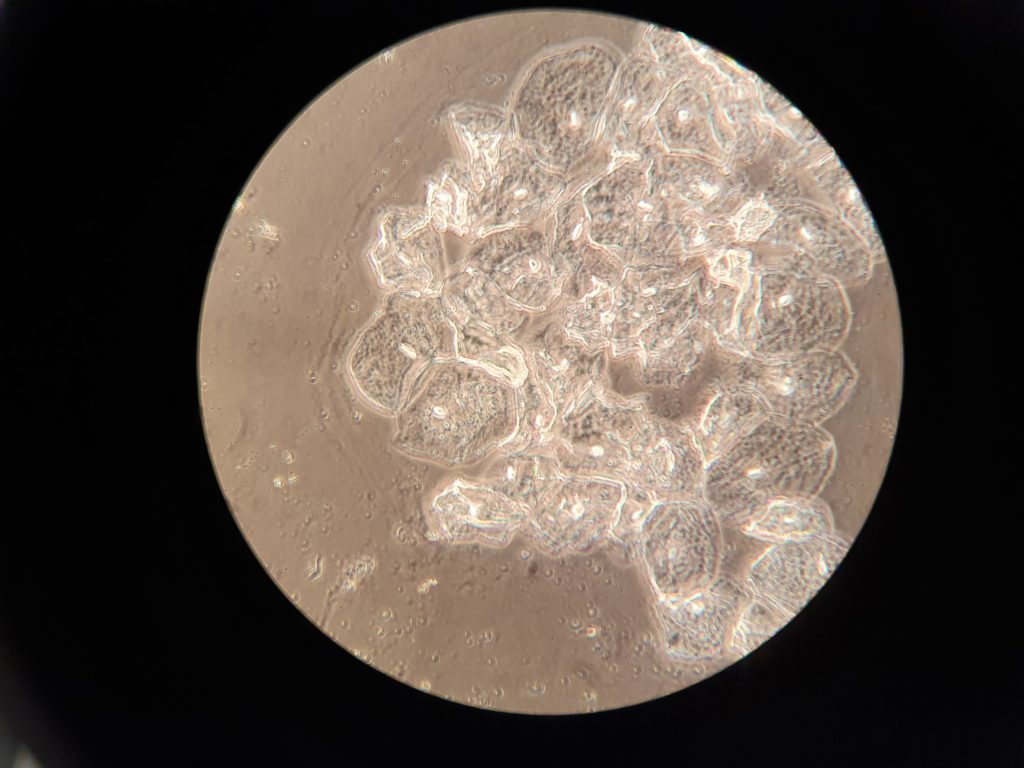

The cells become much more visible in the phase contrast image. This becomes even more obvious when looking at a 40x phase contrast image (400x overall magnification).

So, how did I do this on the BHB microscope? For phase contrast imaging you need a different condenser and objectives with the right phase contrast rings inside them. The condenser for the BHB I have seem to be quite rare (and expensive). I managed to find a potential set for sale at Microscope Wizards, here. However it looked like they were for a different type of Olympus microscope to mine (a more recent one), as the condenser mounted using a dovetail mount which mine didn’t have. It looked to me as though the condenser might be the same diameter as mine, and if so, may be possible to mount in the same way. A few emails later, confirmed the size of it was correct and it should work, so I bought it to try it and thankfully it worked. The condenser came with a couple of phase contrast objectives so gave me everything to get me started.

Sometimes when building and rebuilding equipment original parts aren’t available, and you have to modify things or use something originally designed for another piece of equipment. As scientists we have to look at a problem, break it down in to its component parts and then address each one. The skill set is just the same, and a good scientist can turn their hand to any problem.

If you want to know more about this or my other work, you can reach me through my Contact page. Thanks for reading.