Those that have read my posts before will know that I have a bit of a thing for UV imaging, and that I have been been building a UV microscope capable of imaging down to and below 300 nm. While doing so I’m always on the look out for second hand equipment which can either help with the work, or is of historical value to the whole area of UV microscopy. Today’s post provides some historical context to the development of UV microscopy and shows a couple of the early objectives designed for that job – the Zeiss Monochromats.

The key reason for the development of UV microscopy was the goal of improving resolution – as the wavelength decreases the maximum theoretical resolution that can be reached improves. It made sense therefore to move from visible to UV to see what could be achieved. This increase in resolving power is quite marked, as was noted in ‘Practical Photo-Micrography’ by JE Barnard, 1911, “The objectives made for direct use with ultra-violet light are called ‘monochromats’, and the wave-length for which these are corrected is 275 µµ [275 nm]. The N.A. of the highest power lens in the series is 1.25; but by the virtue of the shortness of the wave-length of the light, the resolving-power is equal to an objective used with white light of 2.5 N.A. – an objective which of course at the present time it has not been possible to produce.”. And nor is it today over a 100 years later. As a side note, the textbook used 275 µµ for the wavelength, and I added the [275 nm] as nm is more commonly used today. As a good friend reminded me, the way the book showed it is a little odd and a more correct way of showing it would be 275 mµ, or as is given on the objectives below 0.275 µ. Not sure why it was shown like this, but wanted to clarify in case of confusion.

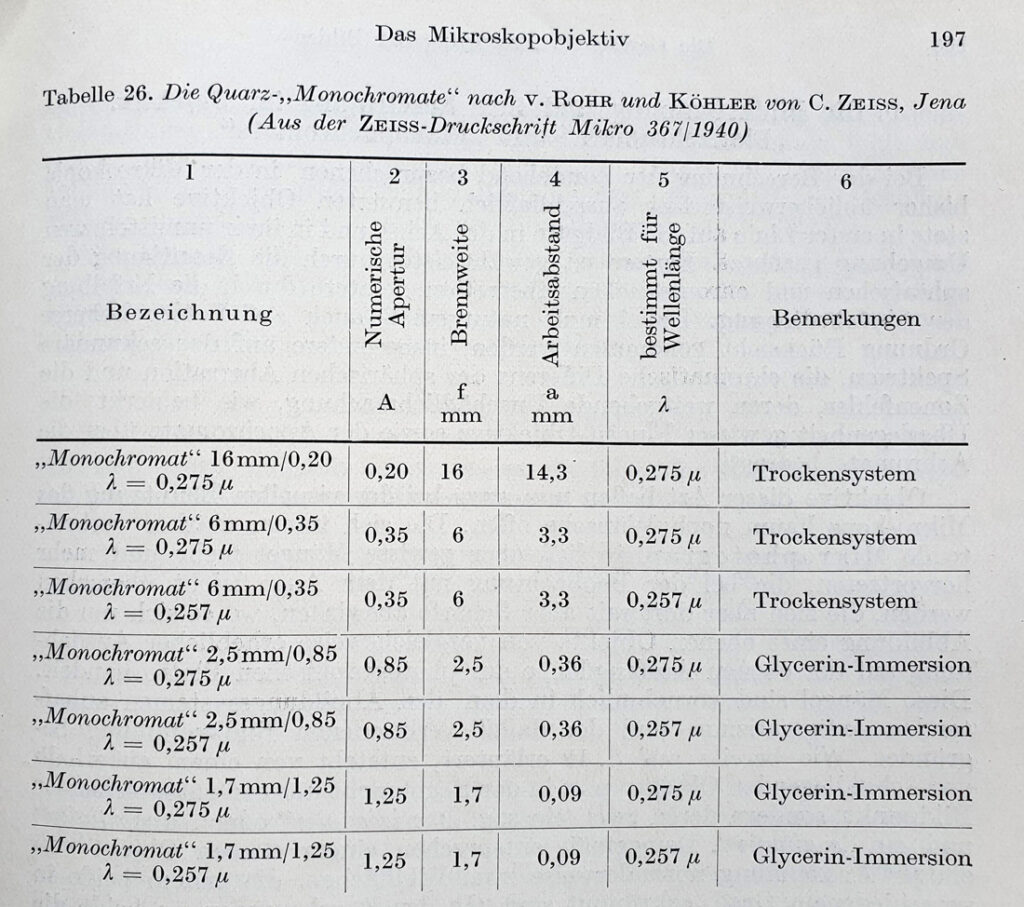

What are these ‘monochromats’? Zeiss produced a range of them with focusing distances from 16 mm down to 1.7 mm, and these were summarized in a table in ‘Die Wissenschaftliche und Angewandte Photographie’ by Kurt Michel, 1957;

The Monochromat objectives were made from quartz lens elements, and were designed to be used dry (trockensystem) or with glycerin immersion. Glycerin rather than oil is used for these UV objectives as it remains transparent even down to 250 nm unlike the oils. They were also designed for use at specific wavelengths in the UV – 0,257 µ [257 nm] and 0,275 µ [275 nm]. These wavelengths were chosen as they are the strong emission lines for mercury (in mercury xenon lamps) and cadmium (from a cadmium arc source) respectively. This does not mean that they can be used at other wavelengths, but it is likely that image quality would suffer as a result. The 16 mm Monochromat might be a later edition to the range, as although it is mentioned in Michel’s book of 1957, it did not appear in Barnard’s text of 1911 (which only mentioned 6 mm, 2.5 mm and 1.7 mm objectives).

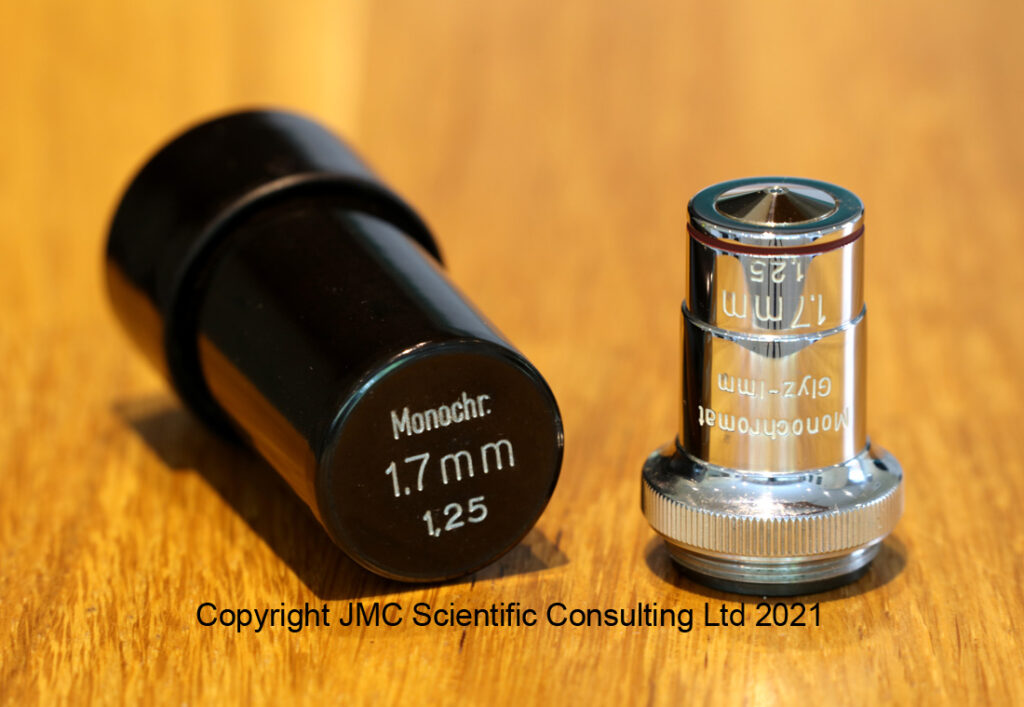

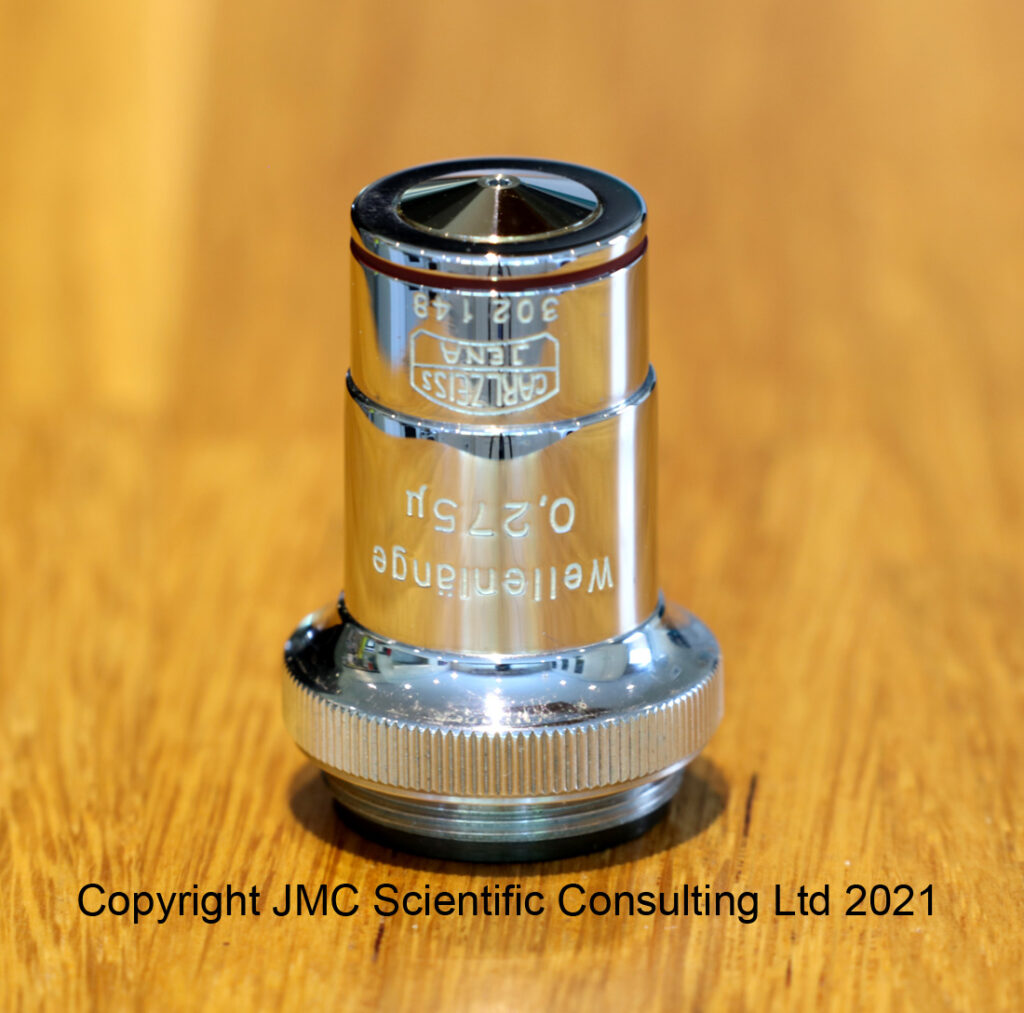

Enough waffle from me, what do these look like? I’ve been fortunate enough to find two of these objectives a 16 mm one and a 1.7 mm one. The 1.7 mm one was for sale on a ‘well known internet auction site’ and has come over to the UK from Ukraine, the 16mm one came from Germany where it became available for ‘the cost of the shipping to the UK’ as it was of no use to the original owner. It’s nice when that happens.

Here’s the 1.7 mm one, with its original objective keeper.

And the 16 mm one;

Both of these were designed to be used with the Cadmium line at 275 nm and both are RMS threaded. In theory they should be for a 160 mm tube length microscope, which is what I have, so I will certainly be trying these out. However it wont be at 275 nm – the lowest I can go with my current setup is 313 nm, and I have no plans on building a cadmium arc lamp (‘elf and safety and all that). I’m expecting relatively soft images, especially when compared with the Ultrafluar lenses, but you never know. Slightly worryingly, JA Needham in ‘The Practical Use of the Microscope’, 1958, said that “The quartz monochromats were corrected for one wavelength (275 mµ) [275 nm] and could not be employed with other wavelengths in the ultra-violet.”. However we shall see after some testing. I’ll also run these through my lens transmission measurement setup to get their transmission between 280 nm and 420 nm. While I’m not expecting any surprises with them (as they should be of all quartz construction), I like to check all new lenses that come in.

The history of imaging and microscopy is fascinating, especially when you dig into the details of how these amazing scientists and engineers tried to push the boundaries of what was achievable at the time. UV microscopy while being a technique that developed over a 100 years ago, is seldom used today as other ways of improving resolution have since come along. However it has huge potential in the field of imaging sunscreens, so is an area I will be continuing to explore and develop. Thanks for reading, and if you want to know more about this or other aspects of my work, I can be reached here.