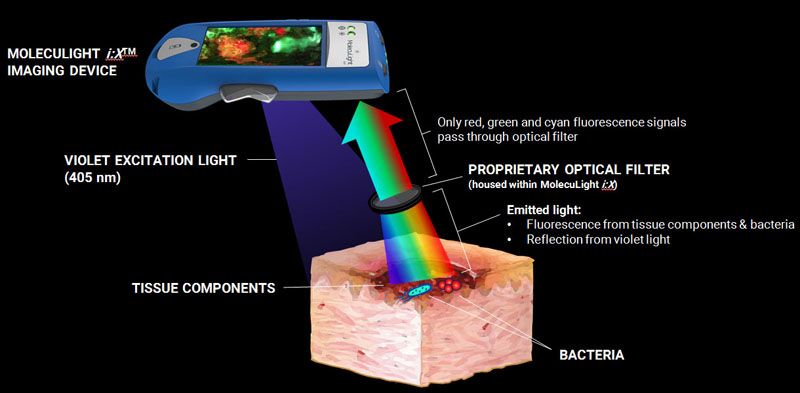

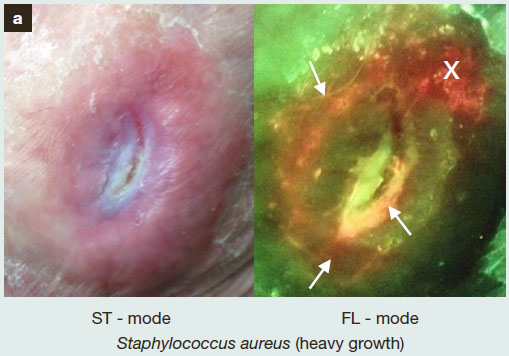

I normally don’t write about devices or methods that I haven’t had direct experience with, as it is hard to get a feel for the technique without that hands-on experience. However, occasionally, I come across a device which I think can have a big impact on improving patient care and includes some elegant science, and as such I’d prefer to get the word out before getting my hands on one to test. Recently while researching a talk on fluorescence imaging of skin, I came across the MolecuLight i:X imager. This uses violet light at 405nm to illuminate the skin and images the fluorescence in the cyan, green and red regions to provide information about bacterial loads and in some cases speciation, and also wound size. The principle behind the device is shown below.

Often, fluorescence imaging of the skin is done with UV light (<400nm). This is the principle behind the use of a Woods Lamp to help with diagnosis of different skin conditions and diseases, or the Courage and Khazaka Visioscan which can be used to image dry skin, as dry skin fluoresces strongly under UVA light. With the MolecuLight i:X they have used a 405nm light source though, in essence using short wave visible light and imaging the resultant fluorescence in longer wavelength visible regions.

They have also thought about how to implement this in a clinical setting, so have made a simple hand held device, designed for use at the point of care, a not requiring an imaging science expert. Even better, and not as common as I would like to see for new devices, the published work has outlined cases which confound the the device as well, to aid with correct interpretation of the images (link to the article). Unfortunately, and far to often, the limitations of a device, and what might confuse readings from it, are either ignored by the manufacturer or not discussed. This inevitably leads to the shouts of “your device is doesn’t work” when analysing some products or in some situations. A proper understanding of the method and the approach should have highlighted potential issues before the study even began, saving time and money in the long run. While it often seems tedious and boring to find out where a device doesn’t work or gets confused, it is only by doing that that the data can be trusted.

Personally I love this type of new device. To take a well known phenomenon – fluorescence – and to move it away from the standard UV based skin examination into the visible illumination, to me at least shows an elegance in the scientific method. Quickly providing clinicians information on bacterial colonization in an open wound can literally be life saving for the patient, so it’s great to see devices like the MolecuLight i:X reaching the market, and I look forward to reading more about it in the future.